The night of the 21st of June 1978, the then Secretary of Treasury, Juan Alemann, received a warning that he would never forget. At 20:20, in the same instant in which Leopoldo Jacinto Luque scored the fourth goal against Peru, which qualified the Argentine national team for the finals of the 78 World Cup, a bomb with a kilogram and a half of explosives went off in front of his house in Amenabar street 1024, in the porteño neighbourhood of Belgrano.

The expansive wave tore off the ground floor window and destroyed part of the living room. The lawyer, right hand of the Ministry of Economy José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, was unharmed. His wife, on the other hand, was slightly wounded. The detonation shattered the windows of almost the entire block. Responsibility for the attack was never claimed by anyone, but 40 years from the fact, Alemann is sure he knows who was behind it: admiral Emilio Massera.

El atentado en la casa del ex secretario de Hacienda Juan Alemann fue noticia al día siguiente en el diario La Prensa.

El atentado en la casa del ex secretario de Hacienda Juan Alemann fue noticia al día siguiente en el diario La Prensa.

The dictatorship’s former staff member's suspicions are not unfounded. For him, the bomb carried the seal of who was master of life and death at the Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA), and was “a message” that came from the heart of that Armed Force because of his recurring critiques of the millionaire numbers the 1978 World Cup Autarchic Entity (Ente Autárquico Mundial 78, EAM) was spending for the organisation of the football championship in the country.

“Massera gave the order to have me killed because I’d messed with the World Cup expenditures”, Alemann assured in a 2005 interview published in Revista Veintitrés. He thought the same thing then. IHe couldn't say it openly for obvious reasons.

Those days previous to the World Cup, the former head of Treasury chose to speak with the media, tired of not being able to control the expenses of his Secretary. The World Cup Autarchic Entity through the 1261/77 decree, disposed of unrestricted funds, based on “reasons of urgency”, and benefited from “reserve in the public broadcasting of their acts”. That’s how it managed to spend ten times what had been previously budgeted.

Alemman estimated the costs at “700 million dollars” and denounced that it was “complete nonsense” for a country that was in an economic situation as delicate as Argentina’s. His declarations forced the President of the EAM, Antonio Merlo, and his vice president, the navy captain Carlos Alberto Lacoste —the real man of power in the inside of the organism— to give explanations and be accountable. This didn’t sit well with a certain sector of the Military Junta, particularly the one commanded by admiral Massera.

The Navy had taken control of the World Cup Autarchic Entity after a vicious inner conflict with the Army. At the beginning of 1976, Videla had put Omar Actis at the front of the organism, a general with a low profile, austere, who had reached the River base in the 40s under the coaching of Renato Cesarini.

Emilio Massera veía en el Ente Autárquico Mundial una plataforma para alimentar sus aspiraciones presidenciales.

Emilio Massera veía en el Ente Autárquico Mundial una plataforma para alimentar sus aspiraciones presidenciales.

The designation of Actis made Massera’s long reach plan shatter to pieces. The head of the Navy saw in the EAM a platform to feed his presidential aspirations, and access to a cash box that he could manipulate at will. With Actis in the middle of it, every thread he had weaved to take control of the organisation went down the drain.

However, the problem was mysteriously resolved. On August 19th 1976, the day in which Actis called for a press conference to explain for the first time his work plan for the World Cup, the general was riddled with bullets from a green Chevrolet truck that carried two people on the front and three in the back.

The murderers threw pamphlets of the “Montonero Revolutionary Army”, with slogans that didn’t correspond to those used by the organisation at the time. The operation had a weird smell: one of the attackers stole the general’s watch, papers and money (something unusual in the actions of the armed platoons that operated in the country), used a heavy and slow vehicle, as if they weren’t worried about the escape, and weren’t intercepted by any of the police roadblocks that had been deployed on that day throughout the entire city. To this day, the doubts point to Massera.

From then on, the EAM 78 did everything exactly backwards as to what general Actis intended. New stadiums were built in Córdoba, Mendoza and Mar del Plata; another three that already existed were renovated (River, Vélez and Rosario Central); a whole new building for the Argentina 78 Televisora (A78TV) station was erected, and hotels, routes and new communication systems were built. The spendings starting flowing with no control.

“The Military Junta made the decision of carrying out the World Cup basing themselves on information that assured that the cost of the works would be between 70 and 100 million dollars. And I doubt that the Junta would’ve made the same decision if it had known that all this would amount to 700 million dollars in expenses”, Alemann came out saying during those times.

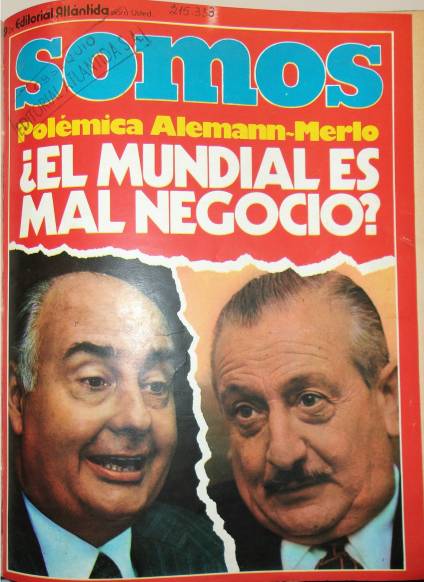

The first months of 1978 were passing by and the controversy was everywhere in the media. On February 10th, La Nación newspaper even published an editorial on the subject and days later Somos magazine, from Editorial Atlántida, which openly operated in favour of the dictatorship, dedicated a front-page to it in its Nº74 edition with the title: “Is the World Cup bad business?”

La tapa de la revista Somos, del 17 de febrero de 1978, sobre la polémica por los costos del Mundial.

La tapa de la revista Somos, del 17 de febrero de 1978, sobre la polémica por los costos del Mundial.

In a five page article, the Secretary of Treasury and the president of the EAM, with the participation of Lacoste, intersected to give their versions of the facts and try to convince the Argentine people if it was worth it or not to organise a World Cup, in a country where inflation had reached 18.7% in two months and recession was hitting hard.

There, Alemann denounced that “the World Cup was inflated” and that “there had been an excess of expenditures”. He said the tournament “embarked all Argentines in a business that would produce awful dividends”, and calculated that the total costs would reach 700 million dollars.

Merlo countered and recognized the spending of “500 million dollars”, claiming that a good part of the works were infrastructure and would remain for posterity. He remarked that the tournament was organised based on “a political decision of the Military Junta” and that “a strictly numerical or financial criteria” couldn't be used to analyse it.

“How much money does it cost to prove that Buenos Aires is the capital city of Argentina to 1500 million people and how much does it cost for five thousand journalists to inform the world about the Argentine reality, after having seen it?”, Lacoste asked himself, trying to give his speech a patriotic halo, to coincide with the “Argentine campaign” the dictatorship had launched. Truth is, his declarations were hiding too much.

The World Cup in Argentina cost around 521,494,931 dollars, almost 350% more than the 150,000,000 dollars the organisation of Spain 82 demanded.

The total represented the fifth part of the free disposal external reserves with which the country counted at the time; the money that was needed to build 98 thousand economic houses, at the cost of five million each, as estimated by the Secretary of Urban Development of the Nation, Máximo Vázquez Llona; or 17 times the budget of the Santa Cruz province, which was around 30 billion.

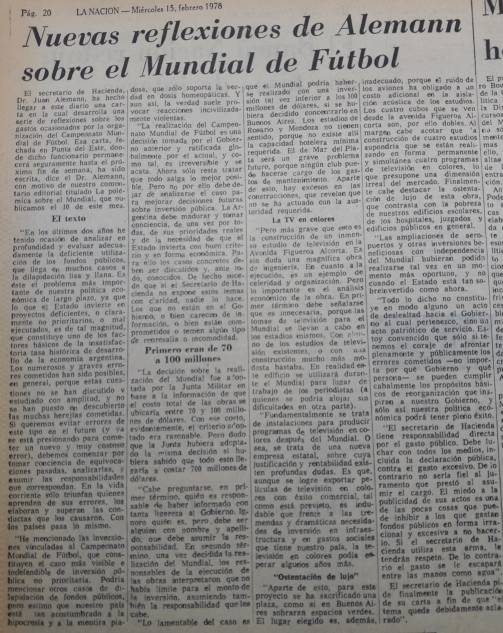

“The organisation of the World Cup should never have been carried out”, sentenced the former Secretary of Treasury. In no uncertain terms, in a letter published on page 20 of the February 15th La Nación, Alemann assured that ever since March 24th 1976 he had had the opportunity to “analyse and evaluate the deficient utilisation of public funds, which in many cases reaches outright dilapidation”.

In that text he considered that the Rosario and Mendoza stadiums made no sense “because not even the minimum hotel capacity exists there” to receive the national teams, tourists and foreign journalists. That the Mar del Plata one would be “a grave problem in the future, because no club can take care of the expenditures of its maintenance”. And criticised the construction of the huge ATC building on Figueroa Alcorta avenue.

“The place chosen is inappropriate because the sound of the planes has forced an additional cost on the studios’ acoustic insulation. (...) The construction of four studios would presume that there are currently being made, permanently and simultaneously, four television programs in colour, which presumes an unreal dimension of the market”, he pointed out. “

The ostentation and luxury of this construction —he remarked— contrasts with the poverty of our school, hospital and court buildings and our public buildings in general.”

La carta de Juan Alemann publicada en el diario La Nación con sus duras críticas a los costos del Mundial.

La carta de Juan Alemann publicada en el diario La Nación con sus duras críticas a los costos del Mundial.

To summarize his idea, the former minister assured that the investments linked to the World Cup “constitute the most visible and indefensible case of non-priority public investment”. “I could mention other cases of dilapidation of public funds, but I understand our country to be so used to hypocrisy and white lies, that it can only handle the truth in homoeopathic doses”. And even then, truth tends to provoke uncivilly violent reactions”, he wrote, without realising that those lines, read from a distance, would anticipate some of what, paradoxically, would happen to him four months later.

The night of June 21st 1978, that premonition became a reality. It was when Mario Kempes broke through on the left, passing to Oscar Ortiz who kicked a centre through the area, letting Omar Larrosa lower the ball at the centre so that Luque could go right into the goal, taking the ball with him. In the middle of the celebrations, the bomb blew up at Alemann’s door. Coincidence or not, the artefact went off in the exact moment in which Argentina made it to the final.

Today, Alemann keeps asking himself the same question: “What would have happened if they hadn’t scored four goals? Would they have gone home with the bomb?”.