The 1978 World Cup Autarchic Entity (Ente Autárquico Mundial 78, EAM) was created by the Military Junta by Act Nº 21.349, which also declared the realisation of the XI Football Championship for the FIFA World Cup of national interest.

EAM began functioning in August 1976, a few months after the coup d’État. It was composed of a president, General (R) Omar Actis, and a vicepresident, Captain Carlos Alberto Lacoste. Six managements divided between the three Armed Forces depended on them. manager of Planning and Control was Commodore Miguel Luciani; Commercialization’s was Colonel Hugo Moldero; General Affairs’, Colonel Walter Ragalli; Infrastructure’s, Captain Norman Azcoitía; Economy and Finance’s, Major Raúl Francisco Veiga; and Press, Tourism and Public Relations’, Doctor Rodolfo de Lorenzo.

The execution of the Football World Championship ‘78, like many other subjects, was a reason of profound conflict on the inside of the military government, and its story was pierced through by some crimes and violent attacks perpetrated by different internal groups, that were presented as a result of the “action of the subversives”.

The first of them was the murder of the first president of the EAM, General Actis, a military engineer who came from serving as an inventor for the YPF Company. A member of the River Plate Club, Actis had a long history of militancy in the sporting entity, first as a football player and then as an active member of the amateur football sub-comission.

On August 19th 1976, only two days before he was supposed to give a press conference on the details of the 78 World Cup project, Actis was brutally murdered. The newspaper La Nación blamed the assassination on an “extremist group” that had intercepted him in the Great Buenos Aires locality of Wilde, while the EAM's president was driving his Chevy to the construction of a housing complex for the Armed Forces. An official statement from the Army also informed that Actis had been intercepted by “four subversive delinquents who fled the scene after the attack” (La Nación, August 20th 1976).

Videla participa del velatorio del General Actis, primer titular del EAM 78.

Videla participa del velatorio del General Actis, primer titular del EAM 78.

Actis was quickly replaced in his charge by Brigadier General (R) Antonio Luis Merlo, who would go on to become governor of the Tucumán province a couple years later, while the discretionary power over the pharaonic funds destined to financing the championship ended up in the hands of vice-president Lacoste, a man of admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera’s.

The press conference Actis was meant to give was given by Lacoste on August the 24th, in the City Council of the then called Capital Federal. The navy man —who the press characterized as a fan of always having a pistol at hand on his desk— claimed there that the 78 World Cup would present Argentina with two challenges: “One being infrastructure, the other, organisation (...). The World Cup’s biggest revenue is in putting the country in a television screen with two billion watchers, and the presence of our country in all the world’s the newspapers” (La Nación and Clarín, August 24th 1976).

The 78 World Cup was, first and foremost, a political event for the dictatorship, giving it extreme popularity on a domestic level and putting the military government on the international front pages as well, where they would have to confront what the regime’s members called an “anti-argentine campaign” against human rights violations.

But these political advantages were not appreciated by the whole government. The organisation of the World Cup also included ambitious infrastructure plans. Among them, a couple of works for the state-run telephone company Entel, the creation of a state-run television company to broadcast the games (Argentina Televisora Color), an airport reparation plan, a road plan, the construction of new sporting stadiums (Córdoba, Medoza and Mar del Plata) and the renovation of others (River, Vélez and Rosario Central). These projects represented, in total and only between 1976 and 1978, spendings of around 500 million dollars.

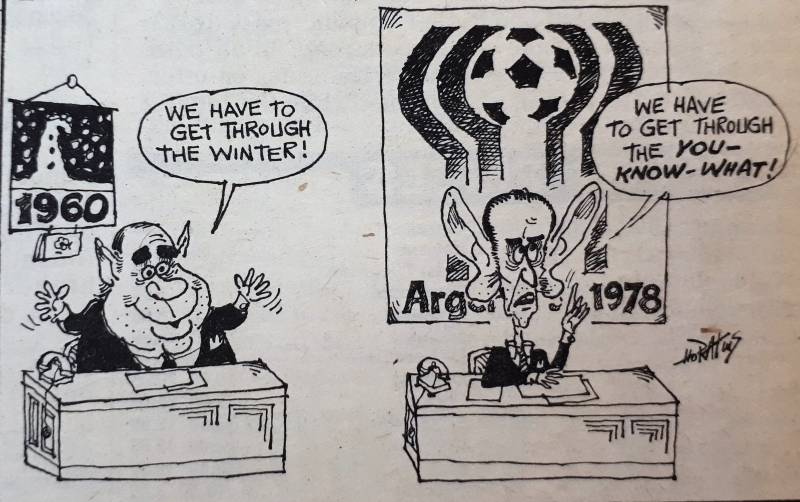

Buenos Aires Herald, 12 de mayo de 1978.

Buenos Aires Herald, 12 de mayo de 1978.

The incredibly high level of spending immediately light up the flame of a conflict which put various members of the EAM against the all-powerful economic team of José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz. How could Economy’s liberals react, them who insisted that the biggest of Argentina’s evils were the State deficit and the inflation, when faced with the astronomical expenditures prompted by the EAM?

In February 1978 these conflicts reached front page of the newspapers.

Juan Alemann, the powerful Treasury Secretary of Martínez de Hoz, denounced that the inflation would go up because of the World Cup's expenses, and qualified the tournament as “a very costly mistake” that the regime “never should’ve made”, a true “ostentation of luxury” (La Nación, February 9th and 15th 1978).

The response of EAM’s president, General Merlo, was very blunt: Alemann had to “first resign if he wished to then criticise”; the General remembered, as did Lacoste, that the championship was “a political event”, and its importance couldn’t be assessed from “the optic of a field such as economy or finances”. The carrying out of the tournament was “an absolute decision by the Military Junta, taken consciously, orthodoxly and with complete liberty” (La Nación, February 16th 1978).

The political benefits that the realisation of the XI FIFA World Cup would have for the dictatorship showed immediately. Once the tournament concluded, Clarín editorialized: “Argentina wants to leave behind, once and for all, the inertia, the pain and the tearing. It wants to walk towards a destiny of achievements and victories”. Meanwhile, the newspaper La Nación warned that “after this World Cup (...) we must keep finding ourselves and reconciling around the nationality’s big common objectives. Today, a calling for greatness awakes” (Clarín and La Nación, June 26th 1978). President Jorge Rafael Videla pointed out that “our country has lived a genuine festive climate that has surprised many visitors who can now testify to the reality of our Motherland, deformed by a perverse international campaign” (Clarín, June 30th 1978).

Evidently, the keepers of public expenditure had been defeated. Juan Alemann suffered a violent attack at his house, at the same time Leopoldo Luque scored the fourth Argentine goal against Perú. It was attributed to the armed organization Montoneros, but the secretary subsequently blamed Massera and Lacoste.

The “World Cup celebration has been magnificent” Treasury Secretary Martínez de Hoz had to accept, finally subdued (La Nación, June 30th, 1978).