Colonel Carlos Alberto Tepedino finished reading the document and signed it. He took a folder from the top of his desk and wrote on the cover: “Urgent.” He placed the information report 40/76 inside and asked to send it as soon as possible to the Director of Intelligence of the Police of the province of Buenos Aires, Osvaldo De Baldrich. What required so much attention was something that for some time had concerned the military: the organization of a possible plan of sabotage against the World Cup.

From the last days of December 1976 the intelligence services of the dictatorship were already monitoring everything that had to do with the football championship. The espionage focused on the movements of the armed organizations within the country and on the steps of the exiles in Europe and Latin America. The Military Junta didn´t want anything to tarnish the tournament with which they intended to show an image of "peace" and "tranquility", while behind the goals the traces of horror were hidden.

The antecedent of the 1972 Olympic Games of Munich obsessed Jorge Rafael Videla. The dictator didn´t want a similar event to occur. The murder of the eleven Israeli athletes in the hands of the extremist Palestinian group Black September was still fresh in the memory and no one in the government even wanted to think about the possibility of such a thing happening. For that reason, the agents of Battalion 601, Task Force 3.3.2, the Secretary of State Intelligence and the Directorate of Intelligence of the Buenos Aires Police were attentive to everything.

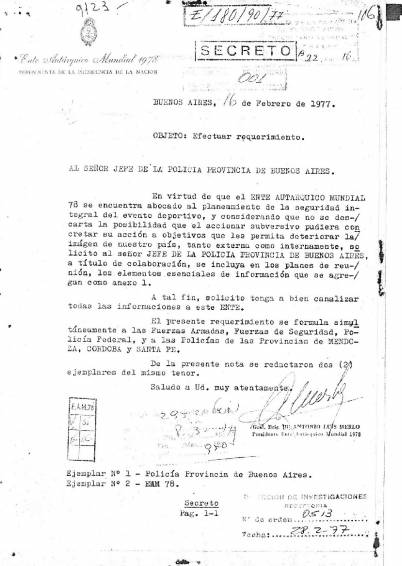

El EAM le pidió informes a las fuerzas de seguridad para saber si se iban a producir atentados durante el Mundial.

El EAM le pidió informes a las fuerzas de seguridad para saber si se iban a producir atentados durante el Mundial.

The investigations began at the beginning of 1977. In March, the World Cup Autarchic Agency raised formal requirements to know if there were going to be actions or attacks against the organizers, the stadiums under construction, the venues, the foreign delegations or the César Luis Menotti Natonal Team. Those days research yielded “negative results”, but some time later, in October, the first Secretariat of Intelligence memos with key information appeared.

“Strictly confidential” report 20/77 reveals that “important members of Montoneros held interviews in Sweden with leaders of international organizations involved in the defense of human rights with the aim of implementing a campaign of psychological action during the 1978 World Cup.”

The memo describes the alleged objectives of Montoneros:

- “Influence representatives of foreign governments somewhat related to the ideology they profess" to “lobby for the non-participation in the tournament.”

- Generate “actions that alter public order during the months prior to the World Cup.”

- “Perform some kidnapping and/or physical attack against a foreign diplomatic member accredited in the country.”

- “To spread pamphlets in different football stadiums abroad, encouraging spectators not to travel to Argentina, wielding a false image of the political-social-economic situation and the lack of individual guarantees.”

The obsession of the military was to know what the largest organization in the country was going to do. The leadership of Montoneros had already announced, through press releases, press conferences and contacts with different media, that not only wasn´t opposed to the World Cup, but that was interested in it being successfully carried out. The Montonero´s leaders remarked, in each of their public appearances, that the contest would allow them to “show the real Argentina” in which there were “tens of thousands of disappeared”, “mass executions”, “kidnappings”, “tortures” and “persecutions.”

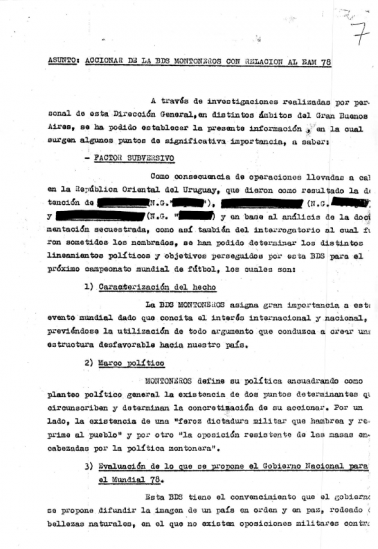

Un informe de inteligencia elaborado a partir de la captura y el secuestro de tres integrantes de Montoneros.

Un informe de inteligencia elaborado a partir de la captura y el secuestro de tres integrantes de Montoneros.

An extensive intelligence report titled “Montoneros action during the World Cup” confirms this. The report says, based on the “capture” and “interrogation” of three people in Uruguay, that Montoneros “has no plans to boycott the World Cup, but they don´t want the government to improve its image.” By decision of the Montonero Military Council, it had been defined that “the only activity to be carried out during the development of the tournament would be only propaganda related”. If armed operations were carried out exceptionally, they should be carried out more than 600 meters from the stadiums.

The text, signed by the official inspector Ricardo Antonio Clérici, of the San Martín delegation of the Secretariat of Intelligence of the Buenos Aires Police, exposes the possibility of “popular demonstrations against the Government”, the distribution of “Pamphelts and brochures” to “journalists and sports delegations” to “influence” their concept of the country and the broadcasting “of the so-called Radio Liberation”.

In previous months of the ’78 World Cup the intelligence agents were following closely the track that interferences in the radio and television signals could occur. The reports of the Intelligence Directorate of the Police assured that the organizations had “a team of national technicians” and “means brought from abroad” to “intercept the transmitting waves” of the systems installed in the stations of “Balcarce (as vital center of the satellite route), Pacheco (as a radio communication node) and Don Bosco (as a relay station)”.

The archives reflect a great display: they speak of the existence of supposed “specialized personnel belonging to Entel, Encotel and the Undersecretary of Communications"; of “infiltrated elements” who tried to obtain information from “the technical networks of the subsectors of Mar del Plata, Rosario, Córdoba and Mendoza”; and they even go as far as to say that the plan contemplated “the possibility of intercepting the transmitting waves from a station mounted on a vessel located at a convenient distance from the Argentine coast or in a land mobile unit”.

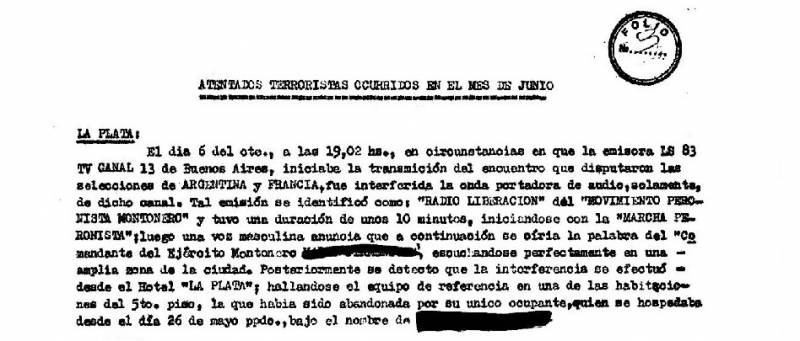

The operations of Montoneros were much more precarious and artisanal. Mario Firmenich had recorded a tape of about ten minutes, which began with a fragment of the Peronist march followed by an extensive speech. The audio was heard for the first time in the downtown area of La Plata, by the signal of Channel 13, at the beginning of the transmission of the Argentina-France match, and eight days later on Channel 10 of Mar del Plata, at the end of the first half of Argentina-Poland.

As it became known later, the first interference was made from a room on the fifth floor of the Hotel “La Plata”, with an antenna built with aluminum rods and a transmitter powered by a Ford Falcon battery. The second, with a similar system, from a department on the sixth floor of Simón Bolivar Street 3259, just eight blocks from the studios of Channel 10 of Mar del Plata.

The resources deployed by the Intelligence Services didn´t anticipate this type of actions and, on the contrary, they focused on unusual and unrealistic issues... such as the possible entry into the country of “Cuban, Japanese and Arab subversive delinquents” that would come from Chile with false passports to sabotage the World Cup; or the arrival of “international narcs” who would bring drugs to “deteriorate the image” of Argentina; or the “3000 or 5000 dollars” supposedly paid to each foreign journalist “for every note, however insignificant, in which references are made to abuses of authority” or where human rights violations were found.

The spies work didn´t anticipate some situations that could have caused a much greater impact on people neither. The internal communications of the Buenos Aires Police show the delayed reaction of the agents who didn´t manage to avoid the impact of an RPG7 rocket on one of the walls of the House of Government or other 17 on the buildings of Battalion 601, the Superior School of Mechanics of the Navy, the Superior School of War, the School of Police and the Commissary 43, among other venues that were attacked surprisingly.

The operatives were considered “successful” by the Montoneros leadership, although the impact they achieved was practically the opposite of what they believed. Not a single line appeared in the national media as a result of the informational siege that the military maintained. So much so that nobody realized that the Argentine flag that was hung for several hours in one of the sectors of the Casa Rosada had nothing to do with the celebrations, but that it was a screen to hide the damage that the RPG7 rocket had left on the wall while the workers replenished the cement.