There’s few days left to the World Cup that’s going to be disputed in Argentina. The director of an Argentine magazine of important reach gets to the door of a simple and sort of battered house in Paris, more precisely, in the number 14 of Nanteuil street. He knocks and introduces himself as an Argentine journalist. The man who answers is young, has a beard, and hesitates in opening the door. Finally he allows him to come in and talks with him about the campaign they carried out to stop the celebration of the World Cup in the Argentina of concentration camps.

The journalist in question is Samuel “Chiche” Gelblung, by then director of Gente magazine. The article is published in a number that went out on the street on the 25 of May 1978, titled “Face to face with the bosses of the anti-Argentine campaign”. Who is he interviewing? The promoters of the Committee for the Boycott of Argentina’s Organization of the World Cup (COBA), who failed in their attempt to stop the realisation of the World Cup in the country, but managed something very important: put in the main newspapers of the world the denounce about the crimes the dictatorship leaded by Jorge Rafael Videla was committing. The face of the enemy.

The first call to boycott the 78 World Cup came in October 1977 from the Le Monde newspaper, in France, the true epicentre of the denounces of violations of human rights in Argentina, as had been detected by the military regime who built there a propaganda and intelligence organ: the Pilot Centre of Paris The initiative began --as the investigator Marina Franco reconstructs in her book El exilio-- from a far left group of French militants. The COBA was built towards the end of that year and had a coordination in Paris --the office that Gelblung visited-- and more than 200 local committees spread through all of France.

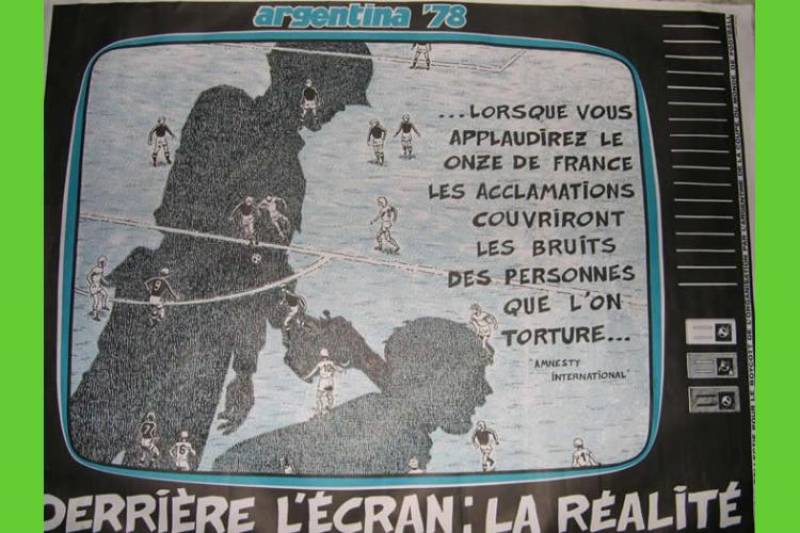

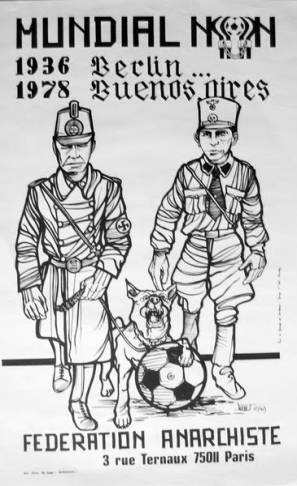

“Will the World Cup, planned for June 1978 in Argentina, take place amongst concentration camps?”, began the calling of the COBA. That was the axis of their campaign, that included a variety of formats and achieved great repercussion. By comparing the World Cup in the Argentina of State terrorism, it made an analogy to the Berlin Olympic games of 1936. Their posters brought back the anti-fascist tradition and were the true image of the opposition to the World Cup. The COBA had many publications but, without a doubt, the most emblematic was L’Epique whose name made reference to the sporting publication L’Equipe, that justified the execution of the championship in Argentina. The COBA’s newspaper managed to sell over 120 thousand copies during the first months of 1978.

The boycott campaign was very effective when it came to adding support to the repudiation of the dictatorship’s actions, although the championship ended up being carried out in Argentina with almost perfect attendance. An anecdote recollected by Franco serves to show the broad support the initiative had. Towards the end of May 1978 and a couple of days before the beginning of the World Cup, two employees of the select hotel Meurice were fired for refusing to carry the bags of vice admiral Armando Lambruschini and his entourage, who had arrived in France to buy guns and ships, seeing as, because of the embargo imposed by Jimmy Carter’s government in the USA, the Junta could only acquire arms from European countries. The young men --of under 20 years and without any political activity-- came to the COBA looking for help. The main French parties built committees to support the workers, their case was first page of the Libération newspaper and shortly after they had to be reincorporated.

The firing of the two hotel employees wasn’t the only thing that took the debate on the situation of Argentina to the papers. The France National Team arrived to Argentina on May the 24th, while in the Gallic Country manifestations against the World Cup organised by the COBA were continuous. The protests ended with some detainees, according to Le Monde on the 26th of May. These marches were an addition to the protests that were carried out every Thursday outside the Argentine embassy in Paris.

Before the team left for Buenos Aires, the exiled people in France tried to get in contact with the French coach, Michel Hidalgo, who received them. They reached an agreement for the players to “sponsor” the disappeared of French origin; “the other French team”, as the posters said.

To boycott or not to boycott?

The Argentines exiled in France participated in all the activities of denouncing the dictatorship, but they maintained an attitude between ambiguous and distant towards the boycott, which was also true in other latitudes. Among the elements that carried weight in maintaining a certain distance from the COBA’s initiative were a mix of nationalist feelings, the popular nature of football and, in some cases, the decision of the main military-politic organizations of not boycotting the World Cup.

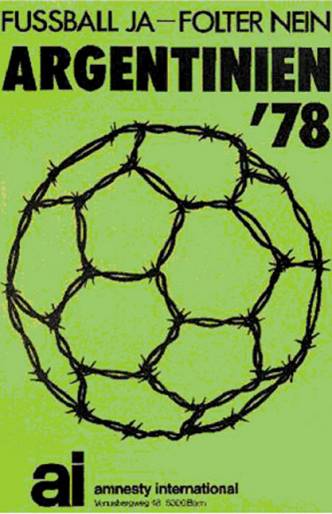

Amnesty International held a similar position to most of the exiled Argentines. The organization founded in London didn’t call to impede the realisation of the World Cup, but rather sent out a campaign whose motto was “yes to football, no to torture”. According to Amnesty, publicity is the worst enemy of torture. That is why they called for all who attended the event to investigate about what was happening in Argentina and then disseminate the information. As Silvina Jensen explains in her book Los exiliados, the organisation denounced by then that there were 15 thousand disappeared and 8000 prisoners.

Beyond France

Towards the end of February 1978, organisations who supported the boycott got together in Paris. After that, a committee in Barcelona was created --describes the investigator Raanan Rein in the book Football Clubs in times of the dictatorship-- while in Madrid Eduardo Luis Duhalde commanded the Committee of Boycotting the Football World Cup.

In a text titled “Argentina ‘78: football and State terorrism”, Duhalde claimed that neither the possibilities nor the conditions for the World Cup to derive into a concentration against the dictatorship were there, considering the militarization that the country would undergo so that the championship would be the “Cup of Peace”.

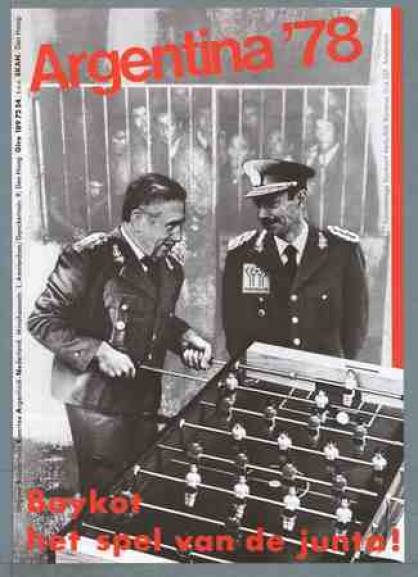

Around the same time, a committee for boycotting the world cup had been created in The Netherlands. The initiative was begun by two variety-show artists, Freek de Jonge and Bram Vermeulen, who didn’t have much success among the Clockwork Orange’s players. The ex-footballers Arie Haan and Ernie Brandts, who visited the ex ESMA and joined the Madres de Plaza de Mayo’s round last April said they remember seeing their show Blood on the poles and the national debate in which the Netherlands was inserted around the participation or not in the World Cup while Argentina disappeared people. “No one will be able to say ‘we didn’t know’ --Freek de Jonge warned them then--. You’ll go to the World Cup as heroes and you’ll come back as collaborationists”.

In their book Fútbol y Exilio, Carlos Pringolini and José Miguel Candia explain that the Commitee of Argentina-Netherlands Solidarity (SKAN) didn’t agree with the boycott but they did use the World Cup to denounce what was happening in Argentina. According to the authors, the members of SKAN kept in close contact with the players of the Dutch national team. On the other hand, the Dutch Solidarity Association (SAM) symbolically joined the boycott and collected funds for the Madres de Plaza de Mayo and the families of the disappeared.