“It is of paramount importance that Argentina begins to speak with one voice in the nations of the world. And that can only be achieved through a highly controlled communications program. (...) The (Jorge Rafael) Videla´s administration must project a new progressive and stable image throughout the world (...) and a successful exploitation of the World Cup can and should 'make Argentina famous'.”

With those words, the Burson-Marsteller US advertising agency was trying to convince the Military Junta in a 155 page document to hire their services. The decision was already made: the dictatorship sought to “clean up” its image, amid the complaints circulating around the world as a result of the systematic violation of human rights in the country. The commanders of the three armed forces had already determined that the best way to achieve that goal was to launch a campaign to counteract the effects of “adverse propaganda” at the international level.

The agreement was secretly sealed, in two different contracts, in June of 1976. One was a 1.1 million dollars contract with the firm Comunicaciones Interamericanas SA, a subsidiary of Burson-Marsteller in Mexico. The other was a 1 million dollars contract with the Argentine company Dialogue according to a series of documents that came to light from the work of the Historical Memory Commission of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Adjusting to present day, it would be something like 10 million dollars.

The agreements were signed by Robert S. Benjamin, president of Inter American Communications S.A., and the vice president of Burson-Marsteller, James Cassidy. Horacio O 'Donnell, Hector Alejandro del Piano, and Eugenio Javier Arismendi from Dialogue S.A. also signed. The first would be responsible for the advertising campaign in Japan, the United States, Belgium, the Netherlands, Colombia, Canada and the United Kingdom; and the second in Brazil, Venezuela, Spain, France, Switzerland, West Germany and Italy.

Videla firmó el decreto 960 con el objetivo de “neutralizar la propaganda adversa".

Videla firmó el decreto 960 con el objetivo de “neutralizar la propaganda adversa".

By then, Videla had already signed decree number 960, dated June 17, 1976, with the aim of “counteracting the psychological action undertaken by international groups directed against the prestige of the Argentine Nation.” And Burson recommended that “the issues of terrorism and human rights” should be “dropped” during those days if Argentina wanted to “take a legitimate position in the world.” “This can only happen with a long-range effort” said the project presented by the company in October 1976.

According to a survey conducted by the agency, more than 400 people from some eight countries around the world said Argentina was “largely a mystery.” “Little is known about the nation in other parts of the world,” the report says in its conclusions. For Burson-Marsteller, the country had to move from that dark image to a much friendlier one. “Many journalists consider the government to be oppressive and repressive, a military institution that deserves to be condemned and not much more,” he said.

The US company offered an extensive program to influence the international public opinion with the idea of “generating a sense of confidence” in the country. The political and social situation and the violence had to be meticulously cleaned up through a plan that included the media, journalists, writers, celebrities, businessmen, consultants, ambassadors and even travel agents. “Those that influence thinking, investments, and travel,” explained the agency.

With that basic idea, Burson worked with the rudiments of public relations: “It is not necessary to speak well of oneself, but it is necessary that others speak well of us.” Thus, the company put together a complete list of newspapers, magazines, and television stations to contact, and another list of journalists who needed to be invited to the country so that “they know Argentina, its government, its economy, its people” and then tell about it.

Para Burson-Marsteller, el país debía cambiar la imagen oscura que daba a una más amigable.

Para Burson-Marsteller, el país debía cambiar la imagen oscura que daba a una más amigable.

The payroll included dozens of journalists, editors, and media sources from each country. Edwin Darby from the Chicago Sun-Times; Michael Frenchman of The Times; Jill Carshaw of the Daily Mail; Jacobo Zabludovsky of Televisa, among others. Each of them had to be given a kit with materials and brochures, “two or three of the president's last speeches”. They were invited to attended organized lunches, walks, guided tours; they were invited to the Teatro Colón, offered trips to each of the cities of the Wolrd Cup. All that so “they would feel comfortable.”

But the strategy of showing Argentina in “peace” and “tranquility” while in the shadows tortures, murders, kidnappings and disappearances multiplied, was not limited to giving that “personal experience” to journalists from different parts of the world; It was complemented with the visit of Argentine journalists to those countries (Holland, Belgium, Canada, Great Britain, the United States, Mexico, Italy, France) to give their “testimony” about the supposed “reality” of Argentina.

Before traveling, Burson-Marsteller was committed to instructing and preparing those chosen to speak, for example, about what had been published abroad and what “really” happened here. Abel Gilbert and Miguel Vitagliano in their book El Terror y la Gloria talk about how the Gente journalist Reneé Salas “toured the editorial offices of Paris Match, L'Express, Le Monde, and Le Figaro 'to know they published notes against Argentina and what arguments they had.'”

The boycott campaign at that height was getting louder in Europe, and the way they were trying to counteract the flood of news that came from outside was not enough. Decree 1871 (July 26, 1977) placed the Pilot Center of Paris inside the organizational chart of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, destined to be an intelligence and military operations center of the task groups of the School of Mechanics of the Navy in Europe.

La Armada le otorgó poderes especiales al director general de Prensa y Difusión de la Cancillería.

La Armada le otorgó poderes especiales al director general de Prensa y Difusión de la Cancillería.

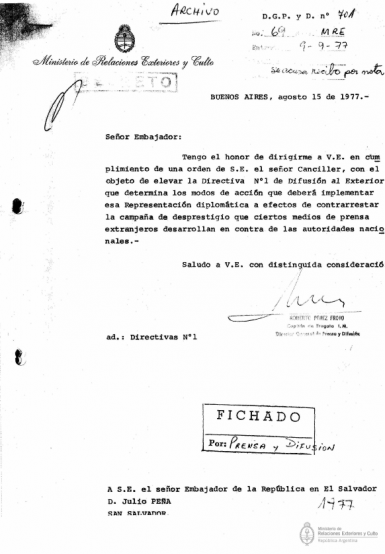

“While Martínez de Hoz signed contracts with advertising, lobbying and public relations agencies, the Navy granted special powers to the general director of Press and Dissemination of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where the Pilot Center of Paris depended. It was the captain Roberto Pérez Frorio, who died under house arrest in 2013. “He frequently visited the ESMA and coordinated the work of the captives subjected to servitude” said journalist Martín Granovsky in Página/12.

The dictatorship´s problem at that time, however, was that it didn´t find the channels to move towards a political transition and it was not even really trying. Burson highlights it and says it clearly in one of his documents in which he analyzes the “implications of terrorism in communications” of the Junta.

“It can really be affirmed that terrorism and the way in which Argentina eliminates it are the only problems that are a barrier between the Videla administration and the approval of the free world” the agency hypothesizes, adding in its analysis: “The unfavorable image then derives either from the conduct of the Government that causes terrorism (SIC) or from the manner in which the government seeks to suppress it.”

For this reason, the North American communications company recommends the dictatorship that it must show that it fights the armed organizations “without infringing basic civil liberties” and with “equanimity”. They also advises that, “when the time comes, the government should invite an international commission to visit Argentina to investigate terrorism and the government's program to deal with it” to prove that the levels of violence have declined.

In this scenario, the World Cup is an ideal opportunity for the future: “Given the enormous coverage of the World Cup by the media, especially television, the event offers Argentina a unique opportunity to present itself to the whole world, to present its people and their way of life.”

Videla bought the whole package and Argentina joined the Burson-Marsteller campaign: films and short films were produced to highlight the benefits of a country in peace and without problems; the streets were flooded with posters of public works and tourist attractions from Ushuaia to La Quiaca; the celebrities, like the multi-champion of the Formula 1 Juan Manuel Fangio or the Nobel Prize winner of Biochemistry Federico Leloir , accompanied Videla in their tours; and the graphic press watered rivers of ink to counter the notes from abroad that spoke of disappearances and crimes against humanity.

The climate of the World Cup undoubtedly helped and the release of popular fervor served as a breeding ground to launch another campaign that a year later became popular under the slogan “Argentines are right and human” while the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights came and found that between 1975 and 1979 “numerous and serious violations” had been committed, a blow to the heart of the military dictatorship and a little transparency, since the lie began to be exposed.