With death on their track, during those days in 1978, there were men and women who took part on the resistance against the dictatorship. A silent resistance without great actions and with no guns. A resistance maybe not as cinematographic or spectacular as the one of bombs or the bazooka shots that impacted on the commissaries and military barracks. A resistance with pamphlets, stickers and graffiti. A resistance with what they had. A resistance with what little could be done.

It had been over two years since the military coup of the 24th of March 1976, and the regime leaded by Jorge Rafael Videla, Emilio Massera and Orlando Agosti had destroyed everything and left a trail of deaths and disappearances on the streets. Since the extermination plan applied by the Military Junta, trade-unions, political, social, and student organizations had been decimated. The majority had lost “cadres”, and with them their ability to act and respond.

The leadership of Montoneros had long ago opted for exile. And in Argentina hundreds of militants had been left loose, “untied”, with no structure, no money, no resources, no refuge, practically adrift. A lot of them, with a certain pride, attempted to maintain their militancy with conviction and an unbreakable compromise with the “fallen”. But their main concern was to survive.

Francisco Rojas remembers that those months “were hard”: “I lived in José C. Paz and I had had to abandon my house. The militants in charge of the area had fallen during a commando hit in March 1978 and, to be safe, we picked everything up and left. I spent many days sleeping on the street, in empty lots, construction works, in the back of some churches. Until a comrade got me a place in Avellaneda.”

“El Negro”, how he was known in “la orga”, was one of the people in charge of the press. He had a writing machine, “one of those Underwoods”, a relic that he had inhereted from his grandmother, and a mimeograph with which he printed the statements. He worked at night until late, with the radio on so that the neighbours didn’t hear the sound of the machines. The next day he went out to hand out flyers by the neighbourhood.

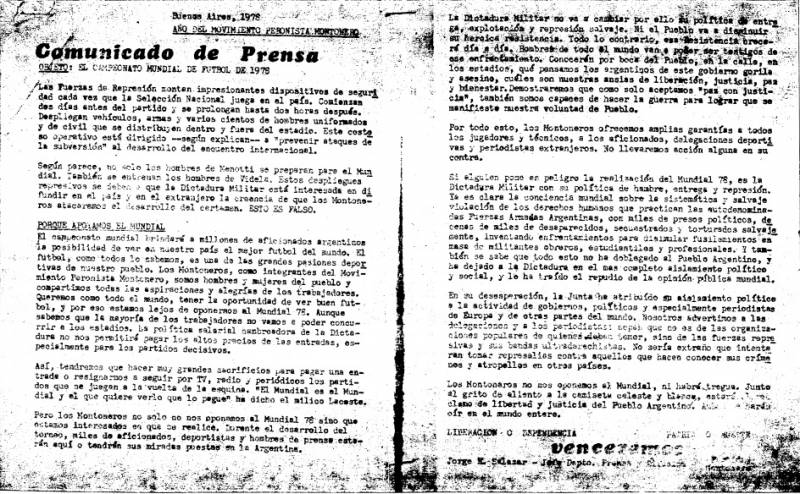

The slogans mostly had to do with the World Cup, although there was also “support to worker conflicts in factories and companies”, he recounts. One of the pamphlets that circulated on those days in the southern area of the Great Buenos Aires said:

The 78 World Cup is an aspiration of the people and we the Montoneros want it to be carried out. The dictatorship intends to use it to tell the world “nothing happened here”, but there are trade-unions intervened, the syndical conquests were nullified, there are thousands of prisoners and kidnapped people, the dictatorship is represses with ferocity and murders mercilessly.

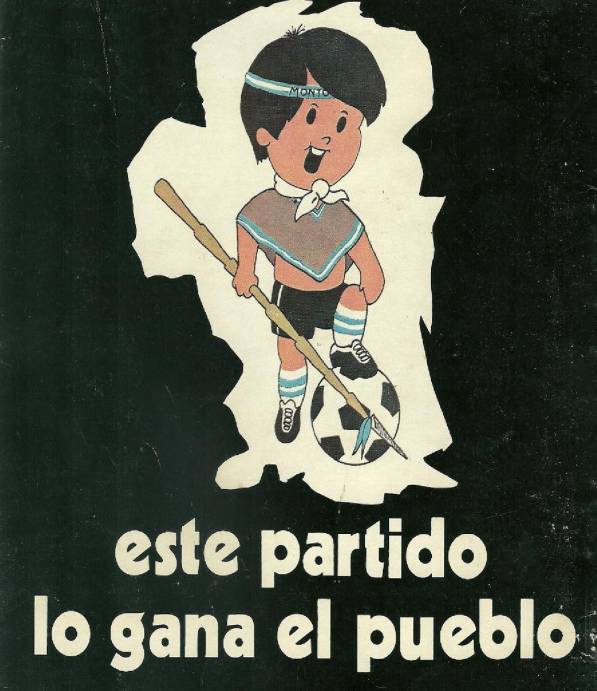

The texts denounced the socio-political situation of the country and were infected by the world championship climate that the streets were breathing. “Argentina champion, Videla to the wall”, “This match shall be won by the people”, “Argentina 78, Dictatorship 0”, “Resisting is winning” were some of the slogans that could be read on those papers of two by three, that carried the World Cup logo and the image of the “Gauchito Montonero”, a replica of Argentina’s official mascot that was dressed with a poncho and held a Tacuara spear.

The World Cup Special Commission, from Mexico, had ordered to make stickers, leaflets with shining paper and bulletins that would later enter the country clandestinely. The intention was to show “the real Argentina” that the dictatorship was trying to hide, and to give the image that Montoneros still existed and had a presence on a territorial level. During the campaign they invested thousands of dollars. Meanwhile, the militants that had stayed in the country received nothing and had to make do.

Marisa Sadi, who by the time was a young 20-year-old pregnant woman, relates in her book Everybody’s shame: “Our main problem was surviving. We looked for things to eat. One day some comrades assaulted a canned meat truck and we spent entire days handing out flyers and eating pâté. We weren’t up for bazooka shots. The military actions were carried out by those who were coming from the outside. We were never told anything, and we found out years later”.

For the militants that still remained in the country, what was left were the “light tasks”. Some of them had received an internal circular from the organization that said: “Each comrade, a mimeograph in their house”, which encouraged the militants to fabricate home made polygraphs so as to make flyers and hand them out during the days of the World Cup.

Marisa remembers that “with a huge belly”, she took the pamphlets, grabbed a gun and took the bus with her husband to hand them out. “You’re insane!” Fernando Diego Menéndez, their chief, told them as soon as he heard about it, once they managed to get linked back with the structure of the “orga”. “There could be a police officer in the bus, a woman who gets her gun out in half a second and puts a bullet right through your foreheads.”

They did it anyway. A little bit out of thoughtlessness, and another bit because to stop fighting had turned impossible after the fall of so many comrades. “Most of the people who were left loose did what they could”, she admits.

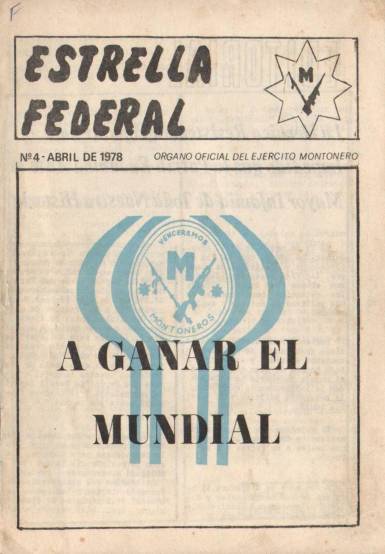

"A ganar el Mundial", rezaba la tapa del N°4 de la Revista Estrella Federal (Gentileza El Topo Blindado)

"A ganar el Mundial", rezaba la tapa del N°4 de la Revista Estrella Federal (Gentileza El Topo Blindado)

Stickers in public restrooms, in train stations, graffiti on some hidden walls at night, and surprise flyer-handing were some of the actions most commonly taken. The conditions which the dictatorship imposed made it so each activity, as small as it was, was transformed into a military operation. Previously they inspected the place, organised the approximation to it, calculated the times and planned the escape.

In some other cases, operation had a different dynamic: a box was left with a spring system actioned by a clock with a temporizer which threw flyers through the air, or the pamphlets were thrown from some motorcycle or car in commercial areas, parks or around the stadiums and places with big gatherings of people.

The day of the inaugural game, some blocks away from River Plate’s field, a flyer handout was organised which didn’t keep to the recommended security measures. According to Sadi in her book Montoneros, the resistance after the end, that’s where Celestino Omar Baztarrica, “Patricio”, fell, along with four other militants of the Peronist University Youth (Juventud Universitaria Peronista, JUP) of the faculty of Law of the University of Buenos Aires (UBA).

A day after that, the military kidnapped his girlfriend, María Josefa Fernández, and “Pelado” Ricardo Freire. The 3rd of June they took Alicia Cristina Amaya, a Social Assistance student, from her house in Caseros. And when the falls began happening one after the other, in the JUP they suspected of the presence of a spy in the group, a supposed ex militant of the Revolutionary Party of the Workers (Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores, PRT), who had shown up one day and simply started attending reunions. Today, all of them are disappeared.

With different logistics, through other kinds of operations, propaganda tasks were also carried out to denounce the atrocities that were taking place in the country. Through letters or parcels with false return addresses and identities, Montoneros pamphlets and bulletins were distributed to journalists, foreign delegations and national football teams.

El "Gauchito Montonero" una adaptación contestataria a la mascota oficial del Mundial 78 (gentileza "El Topo Blindado")

El "Gauchito Montonero" una adaptación contestataria a la mascota oficial del Mundial 78 (gentileza "El Topo Blindado")

On the afternoon of the 6th of June, pamphlets made by Montoneros reached the pre-match meeting of the Argentine national team, in the Mi Dulce Refugio country house, belogning to the Natalio Salvatori Foundation, “apparently addressed to César Luis Menotti”, as informed by a secret report of the Direction of Intelligence of the Buenos Aires Province Police.

In the same document, in which the “terrorist attacks that took place in the month of June” are detailed, there’s an account of the fact that on the 14th and 15th of June something similar happened on the installations of the Country Hindú Club, where the Italy and France national teams were having a pre-match meeting. Publications, magazines and pamphlets reached the place by correspondence.

“A big part of it was intercepted by the security forces that were assigned to the area and the ones that reached the hands of members of the national teams were in their majority destroyed by the players themselves”, says file 11.777 of the 28th of June. The envelopes had as the Córdoba French Alliegance and the Italian Society of Mutual Socorro as return addresses. Other letters came directly from the abroad.

The leadership of Montoneros had set a policy for 1978 that involved the implementation of armed and propaganda actions of such impact that the Military Junta would not be able to cover them up. The handing out of pamphlets, leaflets, the sending of letters, were a part of this strategy that required painstaking work and, of course, a much smaller impact than the bombs in the houses of generals. “Our contribution was less noisy, it was propaganda”, says Rojas.

Even then, he remembers that in the Great Buenos Aires Southern Area, during the World Cup, the workers of Luz y Fuerza were sabotaging and cutting the power in different areas and, in the dark, Montoneros took their chance and went out to graffiti and leave flyers without getting caught. “They were small tasks, maybe without the whole mystic and the talk of feats that you can hear nowadays in some stories of the time, but for us they were very valuable, to feel that we were alive amongst so much death and so much horror”, he closes.