The Peugeot 504 pulled the brakes suddenly and one of its occupants opened the sunroof with a movement. “Alberto” got half of his body out and placed the RPG-7 rocket launcher on his shoulder. He had no time to lose, the operation had to be quick. He aimed at the Casa Rosada and, without hesitating, pulled the trigger. The gas reflux flew back. The missile got up to speed and, after sweeping some metres through the air, it collided with the building. The sound of the explosion startled the military men. Up until that morning, they thought they had everything under control during the World Cup.

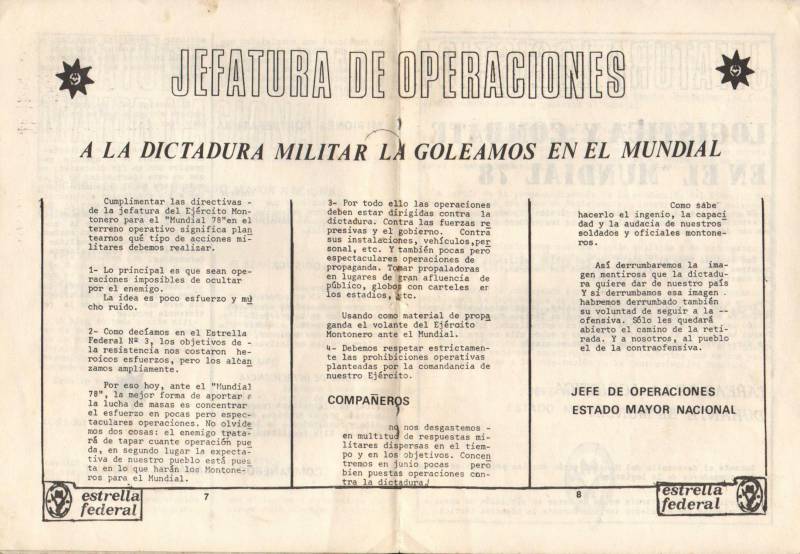

The attack of Montoneros to the Government House the 10th of June 1978 was one of the 25 that took place during that month against different objectives and military buildings. The tactical offensive launched by the heads of the organisation involved the implementation of armed and propaganda actions of such impact that the Military Junta would not be able to hide them. The only thing that was forbidden was to execute operations less than 600 metres from the stadiums and putting the lives of journalists, tourists, foreign delegations, the national teams and the spectators in danger.

The leadership’s orders were clear. “Any action that manages to break the silence barrier will be a victory for the people’s resistance. The main thing is that these be operations which are impossible to hide. The whole idea is ‘little effort and a lot of noise’”, used to say Horacio Mendizábal, head of Montoneros’ military structure on those days.

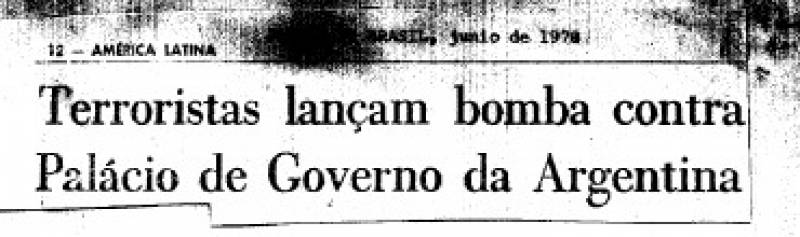

The organization plan, in spite of its level of preparation, would soon begin showing its weak points. The hit against the Casa Rosada had little repercussion on national media. Only a handful of foreign agents published what happened in their respective countries.

The information blackout the dictatorship was imposing functioned in such a way that nobody found out that a group of construction workers covered the hole left on the wall on the first hours of the early morning, working against the clock. To hide the damage, the military hanged an Argentine flag on the hole.

The soviet RPG-7 missiles, while having the capacity of putting down a helicopter or going through a war tank, didn’t generate a big explosion in an instant. The rocket liberated the energy once the wall was perforated. The commotion for the attack was internal and the orifice that was left after the impact was of minor proportions.

The rocket launchers were entered to the country clandestinely. They arrived stuffed in a car that was sent by ship from Europe to the port of Buenos Aires. The owner of the vehicle, a French citizen, travelled to Argentina by plane to make sure the cargo would arrive in perfect condition. The same trip was made by an Englishman who sent a stock of rockets by sea. So as to not rise suspicion, both of them had reservations in the country. They were tourists, they came to see the World Cup.

The platoons received training on the RPG-7 overseas. From the end of 1977 to the beginning of 1978 the combatants were gotten out through Brazil and then moved to Spain. There they reunited with the members of the General Staff of the Montoneros Army. They took part in a course in explosives, but the main training was done on the Paris suburbs. In a country house, a member of security of the leadership trained them on how to handling and use of the rocket launchers.

Once in Argentina, the militants had to follow the plan to a T. They could make no mistakes.

By then, the military had deployed huge security operations. A misstep could mean a fall. And that was inadmissible.

Over the last two years, the organization had suffered a great number of casualties (Mario Firmenich had recognised at least 3000 between 1976 and 1977 in an interview with Gabriel García Márquez). The systematic regime of kidnapping, torture and assassinations was a blow to all of Montoneros’ structures. Some platoons were decimated. Without homes, resources, identifications nor money, they were easy targets for the dictatorship.

In this scenario, the tactical offensive during the World Cup was an attempt to regain lost terrain.

“What is our intention? To force the dictatorship to change strategies, that is, that they abandon the attempt to continue their offensive and have to concede a political and syndical opening”, explained Firmenich in the N°4 of the Estrella Federal Magazine, the official agency of the Montonero Army.

When the combatants arrived back in the country, the offensive was put in motion. The RPG-7 were distributed among the platoons in Mar del Plata and each one already knew the instructions they were to follow. From June 9th 1978 practically one operation per day was executed, sometimes two. The missiles hit against the walls of the Battalion 601 of Intelligence of the Army, the Superior School of War, the School of Police Officers, the Information Service of the Army and the Libertador Building, amongst others.

The rockets were meant to send a message to the Junta: Montoneros was still alive.

The early morning of the 15th of June, the “Martyrs of the Resistance” platoon of the section of Special Troops “Capitán Alberto Camps” launched a missile against the Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA). The operation counted with two support vehicles. The explanation was simple: they were attacking the heart of one of the Armed Forces.

El misil pegó en la parte superior del edificio cuatro columnas.

El misil pegó en la parte superior del edificio cuatro columnas.

The motorcade started close to 4 in the morning. It took Libertador Avenue, always on the right lane and without calling attention to itself. On the other extreme, a relay was supposed to make sure that the access to General Paz was “clean” for the escape. They couldn’t risk there being an external guard in the area.

“Chacho” fired the rocket at Ramallo street. The RPG-7 hit on top of the main building’s entry door, right next to the letters that identified the property. Two cadets who were guarding the place, when seeing the flash, dove for cover. When they got up, the cars were far away, going around the corner to escape. “Alejandra”, “El Flaco” and “Lucho”, meanwhile, were emptying their clips so that no one would follow them.

The operation was a successesful and with no casualties, however the media still gave no place to Montoneros’ attacks.

“For the Argentine press nothing had happened. It was incredible, we’d made such a mess and in the newspapers there wasn’t a single line about it –remembers Roberto Perdía, ex member of Montoneros’ leadership–. Which is why the actual military objective, which was showing the people that resistance was possible, hadn’t been met”.

With the intention of gaining visibility, to the bazooka shots of the RPG-7 they added the collocation of explosives in the houses of brigadiers, generals, colonels, banks and multinational companies’ branches. Following the bombs against the headquarters of the National Development Bank, the car concessionary Ika-Renault in Palermo or the house of the president of the Petrochemic PASA SA there were bigger attacks.

In the town of Castelar, in the morning, close to 5:30 am, an explosive destroyed general Reynaldo Bignone’s house garage, located on the streets Almafuerte and Dardo Rocha. The military man and his family came out unharmed. The bomb damaged the front and the Ford Falcon that was kept inside of it.

In a matter of minutes, the neighbourhood became an anthill. Neighbours, curious people and some foreign journalists got close to see what had happened. No one had an answer, only hypotheses. The next day, newspapers reported very little.

Although the plan didn’t exactly work as they expected, when the World Cup was over Firmenich decorated Mendizábal with the “Order of the Commander Carlos Olmedo” for the role taken against the military forces.

In Paris, smoking Gitanes, Mendizábal detailed publicly the “successes”. Out of all the actions taken by Montoneros during that month, the one that he considered “the most spectacular” was the interference to the transmission of Channel 13 during the match between Argentina and France. In the centre of La Plata, for the first time ever since the organization had become clandestine, a message by Firmenich was heard.

“What we did during the World Cup wasn’t just another operational campaign. We tested out new operational tactics and organisation techniques then that would later serve for the ‘Counteroffense’. And we introduced and used a new armament that hugely increased our fire power”, he guaranteed in a dialogue with Proceso magazine.

What is true is that beyond the epic, the talk about feats, and the decorations behind closed doors, the montonero tactical offensive was forgotten. The dictatorship was so bulletproof by the championship climate that each one of the operations went by as if nothing had happened during those days. The attacks didn’t have the propaganda that the military achieved with their discourse of “peace” and “tranquillity”. On the contrary, they were almost unknown and ostracised.