“FIFA World Cup” it says in its base, and it’s the synthesis of everything the football world longs for. It’s 36.8 centimetres tall and it weights 6.17 kilograms. It’s gravity centre is given by the 3 kilos of 18k solid gold which are what stands out on the central sculpture, two human figures holding planet Earth; and the base, 13 centimetre in diameter with two concentric rings made of malachite, a greenish mineral that shines like diamond.

When the Cup of the World arrived in Argentina in 1978 it was the second hosting country to which it got. The trophy had been crated for the World Cup that was played in Germany in 1974, seeing as in 1970 Brazil had won their third championship and by protocol had become the definitive possessor of the Jules Rimet trophy, named after an ex-president of the FIFA.

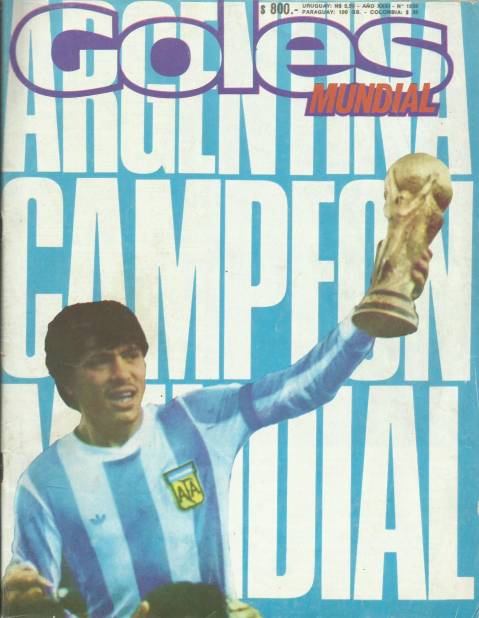

The German national team raised the new cup for the first time with a home victory. That’s why, when the “FIFA World Cup” arrived to Argentina the lower part only held one victorious inscription: “1974 Deutschland”. After the final played in the Monumental Stadium on June the 25th, following Mario Alberto Kempes’ goals, the trophy would be marked a second time: “1978 Argentina”.

The business behind the World Cup

Who would protect, here in 1978 Argentina, that treasure that moves football lovers? The Army’s First Corps was in charge of the security operation organised by the military dictatorship for the Capital Federal and Buenos Aires venues, and the intelligence tasks, under the responsibility of the 601 Battalion, whose members are still being investigated because of the crimes against humanity they committed.

But the trophy didn’t end up in the hands of the military; instead, the 1978 World Cup Autarchic Entity (Ente Autárquico Mundial 78, EAM), leaded by rear admiral Carlos Lacoste, left security in the hands of a private fund transporting company: Juncadella S.A. In his book La larga sombra de Yabrán (1998) the journalist Christian Saenz reveals that the Cup of the World remained guarded in the Juncadella S.A headquarters, on Tres Arroyos street 2835, in the porteño neighbourhood of Villa Mitre.

This firm appearing as the protector of the World Cup isn’t a coincidence but rather proof of the intimate relationship between what began as a family enterprise founded in 1932 by Amadeo Juncadella with a single blinded Chevrolet truck, and the military dictatorship. Juncadella lived a golden age of expansion because of the interest the military had in the business of private security agencies and because of its complicity with the political, criminal and economical plan of the Military Junta.

“The procedure was carried out, at 15:50, by a group of armed people, who wrestled with Demarchi at the door of the morning paper and finally managed to throw him into a blinded truck, similar to the ones normally used for fund transportation. The vehicle parted with unknown destination”, published the newspaper El Día on August 5th 1976. It was an account of the kidnapping of El Cronista newspaper’s ex syndical delegate, Héctor Demarchi. Alberto Dearriba, who was once a writing partner of Demarchi’s, details in the book, Decíamos ayer (de Eduardo Blaustein y Martín Zubieta, 2006) “At the door of the building in the crossing of Alsina and Diagonal Sur streets, they took him forever in a Juncadella truck”. The director of that economical paper, Julián Delgado, would become another disappeared detainee on the 4th of June 1978, three days after the World Cup’s inaugural party, which he had attended.

The civic-military alliance combined terror with business. When the dictators settled themselves in the Casa Rosada the 24th of March 1976, they approved 16 decree-laws such as the “Creation of Stable Special War Councils”, the “Suspension of the Right to Strike” and the 21.265 decree, titled “Allowance of personal security companies”. A year later, the dictatorship dismantled some of the Nación Bank’s services and left the business of transporting to Juncadella, who began managing the tasks with trucks bought to the bank itself, just as pointed out by journalist Daniel Badenes in an article published in La Pulseada magazine in 2010.

Juncadella, Yabrán, Prosegur and Ocasa

The expansion of Juncadella would continue and they’d create Ocasa, a powerful private mail and bank clearing service, by the hand of a young man who Don Amadeo had met as a provider of a computing company: Alfredo Yabrán. “I’m safe. I’m plugged in. When this scam’s over I have work in a company that does bank clearing”, the repressor of the ESMA clandestine centre, Roberto Naya, confessed to the survivor Víctor Basterra during his captivity. Basterra told La Pulseada that years later he’d recognize his torturer in television, as Yabrán’s security.

The expansion continued on the other side of the Atlantic, with strong links to the dictatorship. Sent by Juncadella, Herberto Juan Gut Beltramo —a young man who came from working at Pittsburgh & Cardiff Coal, an armament provider for the Navy and the Army— would create Prosegur S.A, the Spanish filial of Juncadella, on the 14th of May 1976, three weeks after the coup d’état.

In Spain, where the 1982 World Cup would take place —its Organising Comitée would curiously include the vice-president of the EAM 78, Lacoste, by order of the president of FIFA, Joao Havelange—, Prosegur would absorb three years later the Anonymous Society of Security Services (Sociedad Anónima de Servicios de Seguridad, SASS), that was created at the same time by the ex Minister of Social Welfare, José López Rega, the creator of the Triple A, that installed terror, persecution and death in Argentina before the military took over.

Another subsidiary of Prosegur in Spain was AFHA S.A., leaded by Juncadella, seconded by his brother the Argentine Air Force’s Commodore Enrique Juncadella and the Navy’s vice-admiral Oscar Antonio Montes, who commanded the task group 3.3.2 in the clandestine centre that functioned in the ESMA, and who was Argentina’s Minister of Foreign Affairs during the ‘78 World Cup. The society of Montes with the Juncadella family was demonstrated in documents kept by the National Audience of Spain on the investigation carried during the 90s by judge Baltazar Garzón, and made known to the public in May 2016 by the Spanish newspaper Público. The papers revealed a network of societies created by the Argentine civil-military dictatorship to launder money stolen from the victims of repression.

Two days before the National Team played the final against the Netherlands in the Monumental stadium, four blocks away from the ESMA clandestine centre; two days before the trophy kept in the Juncadella vaults was handed in by dictator Jorge Rafael Videla to the captain Daniel Pasarella; Montes, partner of Juncadella and chancellor of the dictatorship, condemned in 2011 for crimes against humanity, denied the terror established by the military dictatorship before the Eight Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS) and maintained that with “the pretext of these supposed human rights violations some governments are sticking their nose in our internal affairs”.