The message came to the office of Goles magazine. “The political line of our publications must be neatly channeled towards a measured and constructive attitude of intelligent critical support to the institutions, to the authorities, and to the men who have and will have the very complex task of leading out to a good destination within. In that sense we will be absolutely intransigent with any journalistic manifestation that irresponsibly foment discontent or tends towards the dissociation of social peace or national unity.”

On Radio Splendid a statement warned that, until the end of the 78 World Cup, there was a need to “refrain from adverse comments on the national team in all programs of the station.”

Censorship was implicit in the rest of the media. They didn´t need an official notification.

La portada de la revista Billiken, también con referencias al Mundial.

La portada de la revista Billiken, también con referencias al Mundial.

“For the outsiders, for all that insidious and malicious journalism that for months mounted a campaign of lies about Argentina, this contest is revealing to the world the reality of our country and its ability to do, with responsibility, important things”, editorialized El Gráfico magazine in its June 6, 1978 edition under the title “Thanks to football.”

Ernesto Cherquis Bialo, at that time chief editor of the most important sports magazine in the country, admits that “El Gráfico had an influence in all the political, social and economic decisions of the country. It was not just another magazine. The influence of the magazine was huge and we knew it. Moreover, El Gráfico made a lot of effort for Argentina to be the host of the World Cup.”

Juan José Panno, former editor of the magazine, sums up his feeling of that coverage at a distance. “Being a journalist at that time was very difficult. In El Gráfico, it was easy for us to have a couple of ideologically similar friends. We were all against the dictatorship. And we all also knew that we couldn´t express that through the magazine, it was impossible. They didn´t need to tell us 'you can´t talk about this or that', we already knew that.”

The EAM 78 had everything under control. It had the most important mass media of Argentina to under its control: Clarín, La Nación and La Prensa and the publishing house Atlántida, in charge of the Vigil family, including Gente, El Gráfico, Para Ti, and Somos. On television, Bernardo Neustadt set the agenda from his “Tiempo Nuevo” show. On the radio, José María Muñoz monopolized the pro-dictatorship speech from his sports show.

“I always said that Argentina was champion despite the dictatorship and not thanks to the dictatorship. Argentina had a great team and its conquest was legitimate. There was no arrangement. That doesn´t exist, it did not exist and it will not exist in a World Cup. Yes, it is true: it would have been better to host the World Cup during democracy, but unfortunately it wasn´t”, says Cherquis Bialo.

The day after the championship, El Gráfico held an exclusive interview with Jorge Rafael Videla and Cherquis was one of the journalists in charge of the meeting in the Casa Rosada. “It was a very short act. We went to give him the World Cup album, a compilation with the best photos of the magazine. We did the same after the consecration in 1986. The talk with Videla was cordial, we were invited by Constancio Vigil, we delivered the album, we made a short interview in his office and nothing else” he recalls.

Ariel Scher is one of the Argentine journalists who studied the link between sports and politics. He lived the World Cup as a fan when he was 16 years old. He spent several hours in line to get tickets for the opening ceremony, and with his father and a friend he saw the final against Holland.

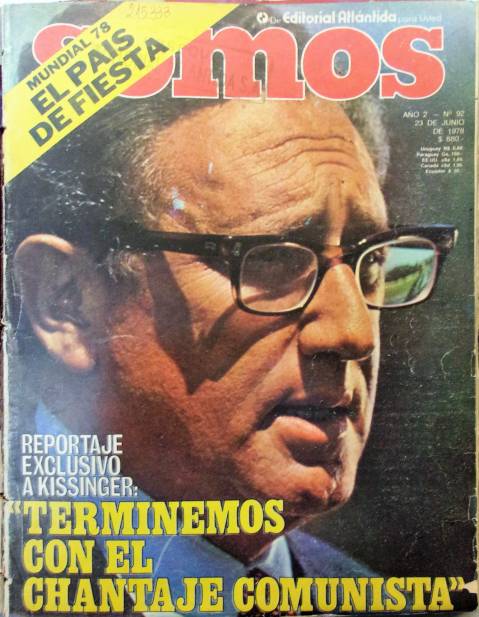

La portada de un ejemplar de Somos durante el Mundial, con una entrevista a Henry Kissinger.

La portada de un ejemplar de Somos durante el Mundial, con una entrevista a Henry Kissinger.

“The 78 World Cup has stories about the game, about Argentina, and about fallacious universes. The dictatorship understood the event as a communication construction. His alliance with media groups facilitated this intention. That's why the story had the nuances we now recognize: exaltation of nationality and a very powerful bond between the triumph of the players and the triumph of the country, homeland and football together. This is something that always existed in Argentina, even before the World Cup, but with the dictatorship was magnified”, says Scher.

For Ezequiel Fernández Moores, the coverage of the World Cup was his gateway to journalism. Without knowing what his job would be, he finished high school and enrolled in the Press Circle in 1976. “Two years later I started working at the NA press agency. I had to cover the 78 World Cup and just out of curiosity I realized that other things happened there, besides football. Unaware of the dimension of horror, which as many people I learned later, it could be seen that some other things were happening and were getting clogged. The World Cup was a key moment” he recalls.

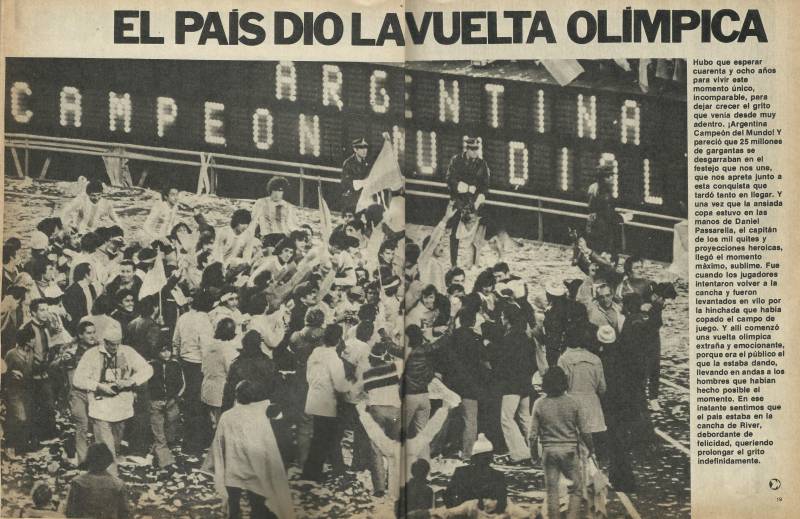

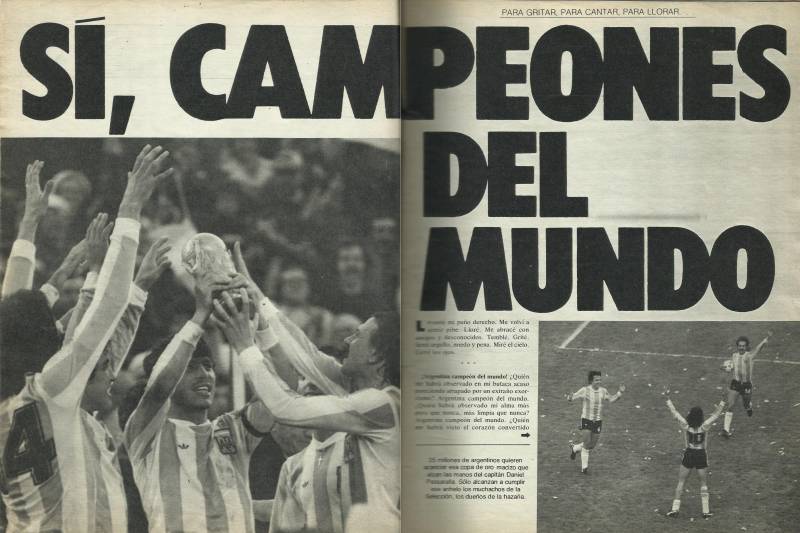

Los festejos por el campeonato del mundo en las páginas deportivas.

Los festejos por el campeonato del mundo en las páginas deportivas.

Panno marks a fundamental difference between the work of the media groups and the journalists who covered the day to day of the competition. “When it was necessary to make a note clearly in defense of the dictatorship or in support of Videla, they knew that they couldn´t ask the 95% of the staff to do that. So, there were the directors of the magazine or Constancio Vigil himself in charge,” he clarifies.

Meanwhile, the media celebrated with impressive sales the consecration of the team of César Menotti. The edition of El Gráfico when Argentina won the World Cup reached its historical record in copies sold so far: 600,000.

“The sport phenomenon is always very tempting to induce submissions and rebellions. And obviously the dictatorship used the media in this sense. For the dictatorship the World Cup was located in such a strategic place in terms of communication as was the Malvinas War”, analyzes Scher.

And despite the passage of time there are wounds that remain open. “I wonder all the time if I could have done something else to uncover what we lived through” Panno thinks aloud.