He was president of the Nation for eleven days, but he never had as much power as he obtained through football during the last dictatorship (1976-1983). He was number two of the 1978 World Cup Autarchic Entity (Ente Autárquico Mundial 78, EAM), but everyone knew he was actually the one calling the shots. The holders of the body in charge of organising the World Cup could change –or be assassinated–, but Carlos Alberto Lacoste remained unabated.

Four days after the World Cup was over, El Gráfico –”The Graphic”, a magazine by the publishing house Atlántida– put rear admiral Lacoste as the first on the list of those to whom Argentine society owed their thanks for the achieving of the title and the conducting of the World Cup. “It wasn’t a time for words, but for actions”, they wrote in the magazine presided by Constancio Vigil. And Lacoste certainly wasn’t only a man of words, but mainly a man of actions –some of them in severe conflict with legality.

He was born on the February 2nd, 1929, a little over a year before the first coup d’état in Argentina. His story was inevitably touched by the military intrusions in the political life of the country. He grew up in Belgrano and was, ever since childhood, in love with River Plate, the football club that to this day still has him among his honorary members, in spite of the fact that in 1997 they put down the portraits of the repressors, and that the sailor died over fourteen years ago.

He studied in the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires (National School of Buenos Aires), a bastion reserved for the well-off middle class with intellectual aspirations. But Lacoste was seduced rather by the uniforms than by intellectuality. At the age of 16 he set about to become one of the lords of the sea. In 1946, he entered the Naval School and in 1948 he graduated as midshipman, exactly a year after Emilio Eduardo Massera, the man who steered him towards the world of football and with whom he weaved his power – even from the shadows of the Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA). Once he had his naval engineering degree, he was an active participator of the Revolución Libertadora –”Liberating Revolution”, the coup that removed Juan Domingo Perón– and, according to Eugenio Méndez, he fought there elbow to elbow along Massera and Rubén Jacinto Chamorro, who would become director of the ESMA during the dictatorship.

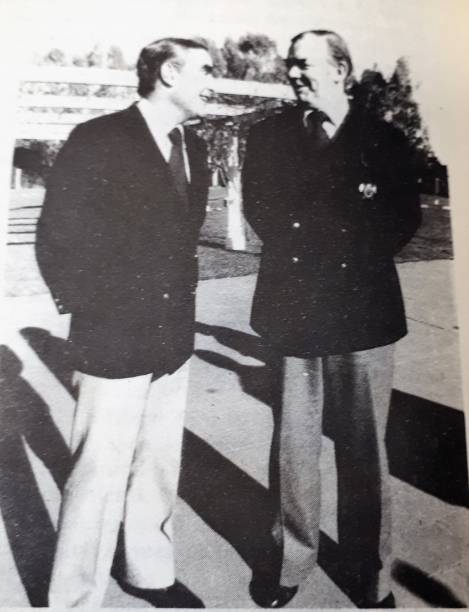

Emilio Eduardo Massera y Carlos Alberto Lacoste. (Alte Lacoste: ¿Quién mató al General Actis?)

Emilio Eduardo Massera y Carlos Alberto Lacoste. (Alte Lacoste: ¿Quién mató al General Actis?)

His links to power weren’t only weaved in the Navy, but also in his family. The Navy man was a cousin of Alicia Hartridge, who Jorge Rafael Videla met in 1946 in San Luis and married two years later. Lacoste married as well, but he became a widower in 1957, becoming the sole guardian of his daughter, María Fernanda. Solitude was short lived. Lucía Gentil, the wife of his friend Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri, introduced him to the woman who would become his second wife: Hebe Angélica Aprile. Hebe had two children from her first marriage and she had three more after marrying Lacoste: Gustavo, Cristian and Mariana. Years later, Gustavo would take part in a scandal linked to the resale of 78 World Cup tickets. One of the many irregularities in which the name Lacoste would be involved.

"El Gordo"

His comrades-in-arms nicknamed the fat framed, 1.85 cm tall man who used to combine an impeccable uniform with cigarettes and an arrogant expression, “El Gordo” (”The Fat One”). In 1974, Massera sent him as his emissary to the World Cup 78 Support Committee, that worked under the orbit of José López Rega in the Ministry of Social Welfare.

After the coup of March the 24th, 1976, Massera put the organising of the World Cup on the table as a priority. His man in charge was Lacoste, but Videla got in the way and designated General Omar Actis for the job. The retired general was in charge of the EAM ‘78 for less than a month and a half before he died, gunned down in Wilde, Avellaneda, the 19th of August 1976. He never got to present his plan for the championship, which looked less pharaonic than the one his successor, Antonio Merlo, a man more permeable to Lacoste, began working on.

The Navy man didn’t attend the funeral of his EAM boss, which Videla did. He was seen standing next to the coffin. With a grim countenance, the dictator seemed to be grieving simultaneously his loyal man, and his own project for the World Cup. Four days after the assassination of Actis, the then captain leaded a press conference in which he unseated the Association of Argentinian Football (Asociación del Fútbol Argentino, AFA) as organiser of the championship and left clear that the World Cup was in the hands of the Executive Power. He spoke of the costs. He said building the stadium in Córdoba would cost 4800 million pesos; the one in Mar del Plata, 4600, and the one in Medoza, 4200.

It was a gesture of transparency that would never be replicated again. The squandering of millions of pesos and the opacity with which the funds were handled was controversial even on the inside of Videla’s Cabinet, with the Treasury Secretary, Juan Alemann leading the debate. In the moment that Argentina scored its fourth goal against Perú in Rosario a bomb exploded in Alemann’s house. Silence is health, said a banner that hanged from the Obelisco at the height of the dictatorship, and another one that was kept in the ESMA’s basement.

With the gun on the table

El Gráfico said it was time for actions. Lacoste believed the same thing.

After the World Cup, the seaman – who in 1978 had gotten an ascension to rear admiral– looked for the help of his friend João Havelange in joining the AFA. There was a problem: he wans’t a part of any footballing entity. The perchance was quickly solved: he was designated vice-president of the South American Football Confederation, in replacement of Santiago Leyden. The next year, he was able to take another step towards controlling football and its business: the vice-presidency of FIFA.

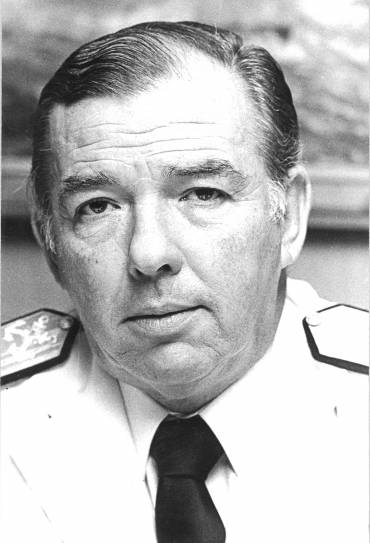

Carlos Alberto Lacoste (AR_AGN_DDF)

Carlos Alberto Lacoste (AR_AGN_DDF)

He wasn’t having much of a bad time in the country, either, and in 1980 he gained access to the charge of rear admiral. Roberto Viola’s de facto government fell because of a palace coup, to which Lacoste, who assumed the presidency on December 11th 1981, wasn’t unconnected. Eleven days later he was stepping down, leaving his friend Galtieri, who would lead the country to the Malvinas War, as president.

He retired as vice admiral when democracy returned. It was clear his power had little to do with the urns. He quit the FIFA vice-presidency in 1984, although he was still a part of the 1986 World Cup Committee. His presence in Mexico was a scandal: the press denounced that a torturer was part of the FIFA entourage.

In Humor magazine, journalist Carlos Ares broke down some of the most notable of Lacoste’s lobbying. The first rehersal was with the family. According to Alemann, Videla was pressed in regards of the World Cup. ¿By whom? The Navy of Massera and Lacoste. The seaman’s hand was also there in 1981 when River hired Alfredo Di Stéfano to replace Ángel Labruna as coach. In his office in the Centre of Naval Electronics, at least another two intimidations took place. One, in 1979, with the goalie Ubaldo Matildo Fillol who didn’t want to sign the contract with the Núñez team under the conditions their directors were proposing. The other with the businessman Benedetto Mosca, who directed the publishing house that published Goles magazine. He asked Mosca for the heads of the journalists who critiqued his mismanagements with the World Cup and who had published an interview with Adolfo Pérez Esquivel before he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980.

The Waning of Captain Piluso

The fall in disgrace came with democracy and brought him many a legal problem. The Administrative Investigations Office (Fiscalía de Investigaciones Administrativas, FIA) accused him of fraud in his administration of the World Cup money and denounced him for illicit enrichment. His friend Havelange came to his aid and declared in judicial premises that he had lent him money to buy a propriety in Punta del Este (Uruguay).

Lacoste, the man of the World Cup, died in 2004 at the age of 75. His remains were buried in the Memorial Park By then, time and the pact of impunity had helped erase the wounds of the old internal conflicts that the World Cup generated in the Military Junta. The proof was that his cousins Alicia and Jorge Videla asked for prayers in his name.