A few days before the 78th World Cup Robert “Bob” Cox, the editor of the Buenos Aires Herald, received a call to go to the Casa Rosada. He went. He was not alone. There were about 30 people, all journalists with decision-making power in the media in which they worked. Before them was the then Minister of the Interior, Albano Harguindeguy who told them that they had to behave because the world had its eyes focused on Argentina. “You have to realize that you must present a perfect image of Argentina” the military instructed them. Bob Cox left the Casa Rosada prepared to disobey, as he had already done. He continued to print –even during the football championship– the only Argentine newspaper that discussed the kidnappings and disappearances in the midst of a dictatorship.

Bob Cox was 26 years old in 1959 when he arrived in Argentina and got a job as editor of the Buenos Aires Herald, a newspaper founded in 1876 that was read by the British community. He assumed the role as editor of the newspaper in 1968. In his hands, especially during the years of the dictatorship when the rest of the media wrote about other things, the Herald gained national and international prestige by being the only one to publish the stories of human rights organizations. Why was that? Because Cox disobeyed.

Robert "Bob" Cox (Foto: Joaquín Salguero)

Robert "Bob" Cox (Foto: Joaquín Salguero)

Shortly after the military took office on March 24, 1976, the telephone rang in the Azopardo Street office. Cox listened and listened to the message: you can´t write about kidnappings and murders. Nothing. Not a word. He spoke with Andrew Graham Yooll, one of the editors who later had to go to the exile, and decided that he was going to publish all the cases in which a relative of a disappeared person presented himself with a complaint made before the Justice.

The office of the Herald was a couple of blocks from the Plaza de Mayo. The Mothers didn´t take long to get to the offices to denounce the abductions of their sons and daughters. It was the only newspaper that opened its doors and Cox was the only editor willing to dedicate a cover of the newspaper to save a life. The newspaper ceased to be a media for the British community and became a newspaper that was bought even by people who didn´t understand a word of English, to read the only part that was printed in Spanish: the translation of the editorial.

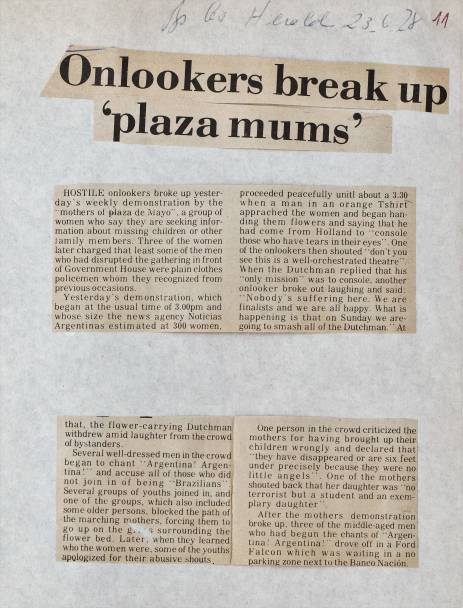

Espectadores rompen marcha de las Madres de la Plaza. (Archivo periodístico del CELS)

Espectadores rompen marcha de las Madres de la Plaza. (Archivo periodístico del CELS)

“Nothing appeared in the newspapers, except in the Herald, which was a very small newspaper written in English. Most of our readers were foreigners from the English-speaking community in Argentina. We had begun to confirm that they took people away and had them in secret centers. That's how the Herald gained importance” says Cox 40 years later, in his apartment in Recoleta.

In 1978, the Herald brought together in its pages the sporting joy with the accusations of the disappearances, as two parts of the same piece that couldn´t be separated. “The World Cup was a moment of horror and at the same time a moment of glory” says Cox. On the Sports page they counted the days for the beginning of the World Cup under the headline of "World Cupitis” (Mundialitis)”.

“I enjoyed writing about the World Cup. I enjoyed the matches. For a moment, although I knew what was happening, I could forget it. I thought there might be a chance that the military would become decent and stop, but they didn´t. They continued, not as openly as before but they continued”.

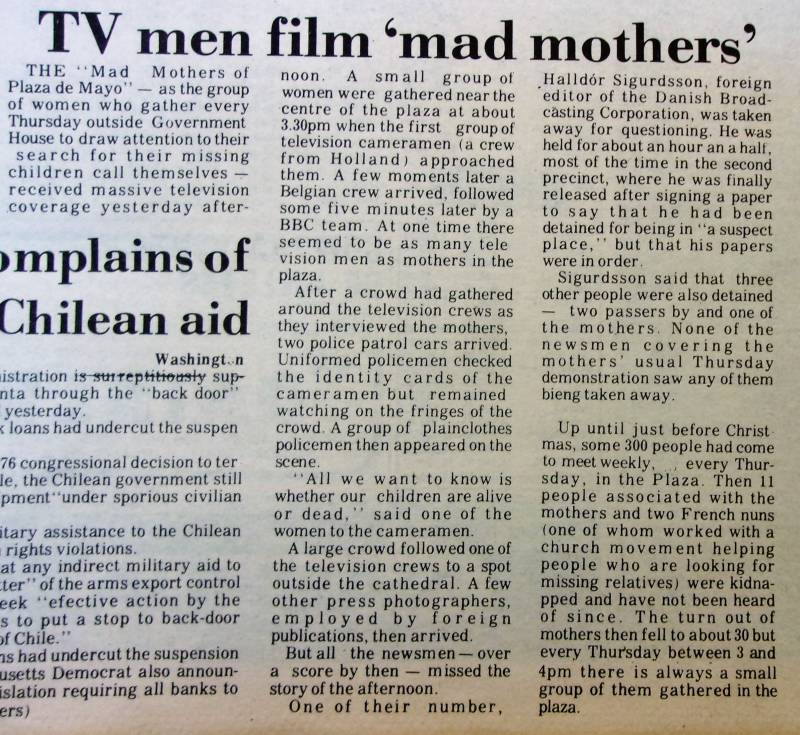

La televisión filma a las madres locas. Tapa del Buenos Aires Herald del 3 de mayo de 1978.

La televisión filma a las madres locas. Tapa del Buenos Aires Herald del 3 de mayo de 1978.

The expectations of Cox on the World Cup could be summed up in, on the one hand, that for the Junta the celebration of the championship meant an end of the clandestine repression era. On the other hand, that the arrival of foreign journalists willing to report what was happening in the country, and not appear in the main media, would generated such pressure that the Junta couldn´t deny the crimes.

The appeal to the foreign press pressure appears clearly in the editorial “A political time bomb”, published on May 17, 1978. “Although its presence [that of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo] has been to a large extent ignored by the local press (apart from the lists requesting information about missing people that have appeared in paid notices, and the arrest last year of about 200 people at a demonstration outside the Congress), they are part of the schedule of almost all visiting journalists and television teams. Their sad story has gone around the world. Their image on television screens will be the image of Argentina during the next Football World Cup”.

Editorial del Buenos Aires Herald. 17 de mayo de 1978

Editorial del Buenos Aires Herald. 17 de mayo de 1978

The Herald, in Cox´s hands, continued publishing cases of disappearances during the World Cup. Also, published the accusation of the kidnapping of Julian Delgado, the editor of El Cronista Comercial and Mercado magazine. Delgado disappeared on June 4, just three days after the start of the World Cup. None of their media gave the scoop on the kidnapping. The Herald, the great little English newspaper, did it on June 13. The boldness earned Cox a new invitation to the Casa Rosada by Harguindeguy, who reprimanded him for the publication and told him that Delgado had committed suicide, as David Cox reconstructed in the book Dirty War, dirty secrets. The anger of the Junta and of the partners of Delgado with the editor of the Buenos Aires Herald can also be traced in the documents declassified by the United States.

During those days, Cox not only went to the Government House, but also sent letters demanding information. On June 12, he wrote to the number two of Harguindeguy, José Ruiz Palacios, asking him for information about the kidnappings of the Eroles family. Two days later, he asked to know what had happened to Alejandra Naftal, at that time a high school student who had been abducted from her home.

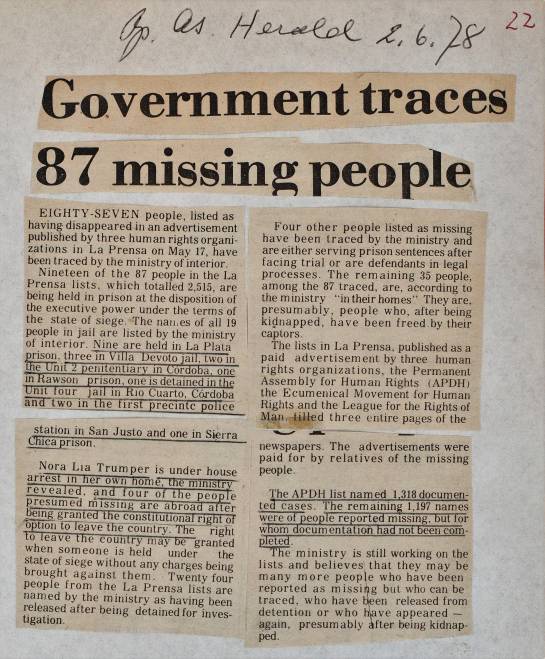

Gobierno encuentra a 87 desaparecidos (Archivo periodístico del CELS)

Gobierno encuentra a 87 desaparecidos (Archivo periodístico del CELS)

The investigation or the publication of the facts denounced by the relatives of the disappeared didn´t make of the Herald a newspaper with sympathy to the left. In an editorial printed three days later, he demanded that the de facto government use legal repression against the leftist armed groups, which Cox and his colleagues defined as terrorists. “The visiting journalists will soon see that this is not Russia. The 'mad mothers of Plaza de Mayo' wouldn´t be allowed to be even close to the Red Square. You will see that Argentina is an exceptionally peaceful place, not at all similar to the ferocious military dictatorship on which they have been reading in the ultra leftist press. But they will soon be able to ask embarrassing questions such as: why do they keep Professor Alfredo Bravo, the leader of human rights, detained without charge? And why has Adolfo Pérez Esquivel been arrested more than a year ago without charge, a man opposed to the violence who had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize 1976?”

Tapa del Buenos Aires Herald del 26 de junio de 1978.

Tapa del Buenos Aires Herald del 26 de junio de 1978.

The liberal views of the Herald of the Argentine situation couldn´t prevent the repression from encircling its director. Cox could see Argentina-Holland on June 25, 1978, and he wrote about it. “The jubilation was so great that the massive celebrations of 1945 for the end of the war in Europe paled before the frantic joy that seized the twenty-six million inhabitants of the country” he wrote. He went out with his wife, Maud, and their five children to celebrate the triumph through the streets of Recoleta. “Those not jumping are Dutchmen” his neighbors shouted. Confetti fell from the balconies and people used pans to make noise to celebrate. The joy was short lived.

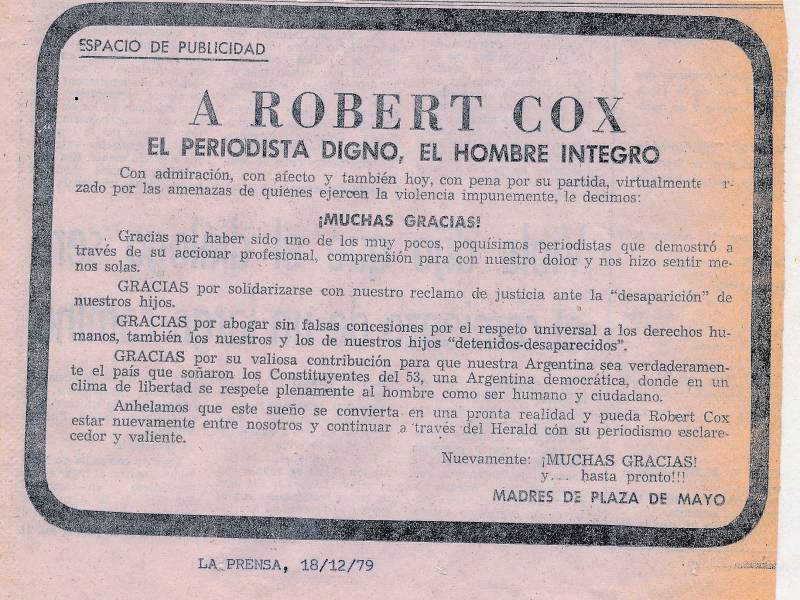

In December of the following year, his family left the country. A letter threatening another of his children was the breaking point for the editor, who had been taken twice to the clandestine center that operated in the Federal Security Superintendence, and suffered the cells of the dictatorship in person. On December 16, 1979, he wrote his last editorial in the Herald. Two days later, the Mothers addressed him in the newspaper La Prensa, “Thank you for being one of the very few, very few journalists who showed through their professional actions, understanding for our pain and made us feel less alone”.

Solicitada de Madres de Plaza de Mayo. 18 de diciembre de 1979, La Prensa (Archivo de Emilio Mignone)

Solicitada de Madres de Plaza de Mayo. 18 de diciembre de 1979, La Prensa (Archivo de Emilio Mignone)