Horacio Domingo Maggio had been detained in the heart of hell for 396 days. A hell that even he, a Christian, as he defines himself, knows that has no equivalences with the one described in his religion. “The terrible wait for the trial and the burning fire will soon devour the rebels” says the Bible. In the School of Mechanics of the Navy (ESMA) there is no trial. All are guilty and for the dictatorship there are only enemies, unless they prove otherwise. The General Íbero Manuel Saint-Jean, governor of Buenos Aires, made it clear in May 1977: “First we will kill all the subversives, then we will kill their collaborators, then their supporters, then those who remain indifferent and, finally, we will kill the shy ones”. When Saint-Jean said this, Horace, “Nariz”, had been three months kidnapped.

In the ESMA, Horacio thinks about escaping. In his bunk, in that filthy room where, at night, he and his companions feel the rats walking on their injured bodies. He kept a book by the French journalist Gilles Perrault, The Red Orchestra, published in 1967. It tells the story of an espionage network that was formed during the Second World War to combat Nazism. On one of its pages, a police report notes that the leader of an organization “apparently had the complete list of all houses with double exits in Paris”.

On March 17, 1978, Captain Jorge Acosta, aka "el Tigre", allowed a distraction to Horacio, who had earned his trust. He leaves the ESMA accompanied by a young, low-ranking military man, with the mission of buying pens and paper for the “Pecera” (the fishbowl), an office sector in which the hostages were forced to produce reports of interest to the military. Horacio gets out the car and remembers, immediately, the book that accompanied him during his captivity. He identifies a two doors shop and enters in. He vanishes in the back, while its custodian is in the front. Aware of the news and enraged, Acosta checks the fugitive's bed. There, he finds the book that had inspired the “Nariz” (Nose).

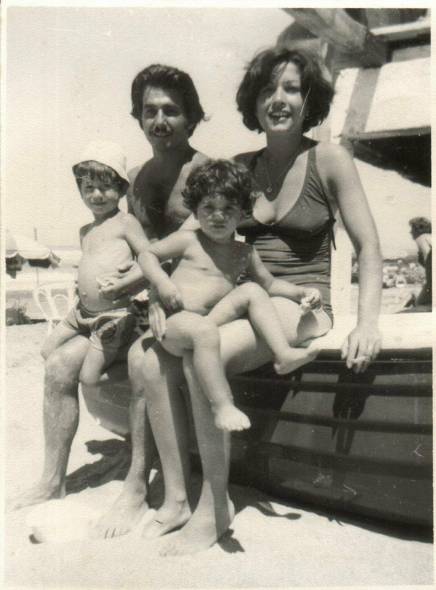

Horacio flees. He remembers his native Santa Fe, the politics talks at the National School, his coworkers choosing him as a delegate of the Banco Provincia, his militancy in Peronism. He remembers his mother. He remembers Norma, his partner. He remembers Juan Facundo and María, their children.

On April 12, 1978, Horacio begins to write, and doesn´t stop. He writes he was kidnapped. That he was tortured for 15 days. That he had a cardiac arrest and that a doctor revived him so that they could continue with “the cattle prod, the machine and the submarine”. That he heard his captors saying the way in which they got rid of the bodies: they gathered 6 or 7 bodies in a car to pepper them and then set them on fire. That they also were throwing people to the sea. He identifies some of the kidnapped of the ESMA, among them, the French nuns Alice Domon and Leonié Duquet and the young Dagmar Hagelin. He also identifies several of the repressors. He sends the letters to the embassies of France and the United States; to the UN; to the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights; to Amnesty International; to unions, journalists, businessmen and the Military Junta. Also to two foreign news agencies: the Agence France-Presse (AFP) and the Associated Press (AP). He also tells all this things to journalist Richard Boudreaux.

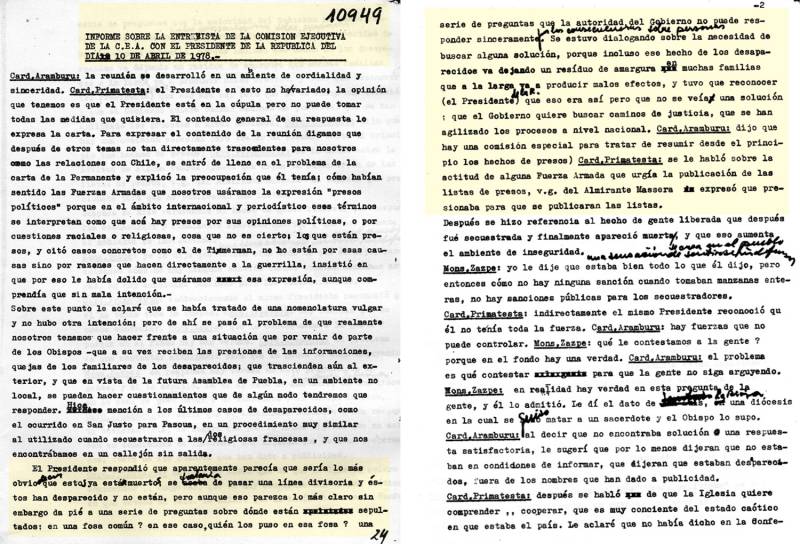

Horacio says that is his “moral obligation as a Christian” to denounce all he has witnessed, and sends his text to the highest authorities of the Catholic Church in Argentina: Juan Carlos Aramburu, Raul Francisco Primatesta and Vicente Zazpe. Five months before his abduction, the three had written a document supporting the dictatorship “with understanding, with adhesion and acceptance too”. They added that “despite the Government's remarkable efforts on behalf of the country, there seem to be a lack of authority”. The ecclesiastical leadership was faced with a dilemma: “A compromising silence of our consciences that, however, would not serve the process either” or "a confrontation that we sincerely do not want”. Two days before Horacio began to write his denounce, the three had met with the Military Junta, which confirmed them that the disappeared had been killed. They had the executioner's version. The “Nariz” threw them the victims´ version. They decided to remain silent.

The ‘78 World Cup begins while the Military Junta is dedicated to counteract the denunciations of human rights violations. Juan Facundo Maggio is six years old. He gets in a car at Caseros. He sees trucks and buses full of Argentine flags. At a certain time, the car stops its march. The door opens and he sees it: after more than a year, his father, Horacio, is reunited with them. In the following weeks, as Argentina advances in the World Cup, he tries to resume his family life: in spite of being one of the most urgent objectives of the ESMA task force, every afternoon he waits for Facundo outside his school.

The National team wins the World Cup and the title gives oxygen to the Military Junta. A few blocks from the River Plate stadium, epicenter of football glory, hell was still working. In hiding, knowing that his life hung in the balance, Horacio celebrated the championship with his children. María remembered those celebrations during her testimony in the ESMA Megacause. “That´s is one of the memories I have. Being with my dad celebrating of the World Cup, of being with him because he was sure that day they were not going to look for him”, the young woman told the court. Horace wasn´t quiet while being underground. In those days, he called the ESMA from public telephones: “There's going to be a Nuremberg for all of you, murderers” he shouted.

He was killed on October 4, 1978. “El Tigre Acosta called us and made us all pass, one by one, in front of Horacio's body”, says Alicia Milia, an ESMA survivor. The “Nariz” letters served as evidence in that trial and in those that followed. In addition to his testimony, there were also maps of the largest clandestine detention center that existed in the country. Horacio could hide, but he chose to denounce what was happening. He did it when, as León Gieco sings, “the churches were silent and football ate it all”.