Officially, the world championship that took place in Argentina begun at midday on the Thursday 1st of June 1978 in the River Plate stadium. A series of choreographies in which, at the beat of military marches, hundreds of young students wrote with their bodies in the playing field, was the central axis of the inaugural ceremony of the Football World Cup of 1978. Jorge Rafael Videla, president of the Military Junta which was the country’s terrorist de facto government since March the 24th 1976, spoke about national pride, peace, and the good image the country was showing the world. Far from contradicting him, FIFA's president, João Havelange, complimented the organisation. Meanwhile, about 40 blocks from the Monumental stadium, the Madres de Plaza de Mayo walked around the Plaza de Mayo Pyramid to claim for their disappeared sons and daughters. Without their knowledge, a lot of them remained kidnapped in the clandestine centre that functioned in the Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy, located a few metres from River.

Claudio Morresi was a teenager who worked with his uncle delivering chickens and eggs, who trained in Huracán’s base to make his dream of becoming a professional player come true —something he would achieve some years later— and who had been in line for many hours at the door of the Argentine Football Association (Asociación Argentina de Fútbol, AFA), to fulfil another dream: “To watch the best players of the world live at the World Cup”. However, the joy was tarnished by “an immense contradiction”. Two years before, his brother Norberto Morresi, a militant in the Union of High School Students (Unión de Estudiantes Secundarios) had been kidnapped with only 17 years of age. Claudio owes his participation on the Relatives of the Disappeared and Detained for Political Reasons (Familiares de Desaparecidos Detenidos por Razones Políticas) group for the claim of Norberto’s return alive, for Memory, Truth and Justice for him and all the other disappeared.

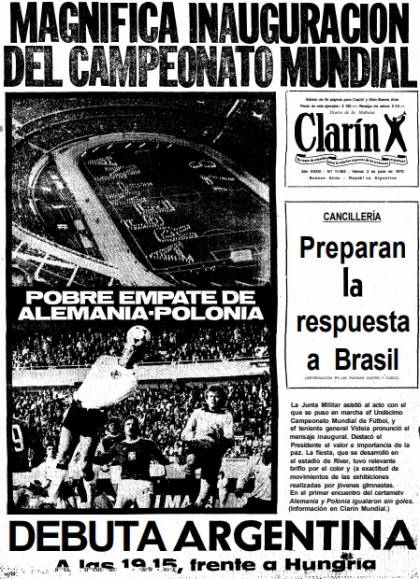

The long paraphernalia began at noon. Days before, the newspaper La Nación had published the schedule of the day, with precision as exhaustive as it was ridiculous: among the times of the beginning of road operations and of the turning on and off of the stadium’s lights, the published chart mentioned that the Monumental’s doors would open at 10 for the public’s entrance, at 13 the ceremony would begin and at 15 the match between Argentina and Polonia, which ended with a boring 0 to 0.

The schedules shifted a little bit. Journalist and Writer Pablo Llonto says in his book La vergüenza de todos that the Military Junta consisting of Videla, Emilio Massera (in charge of the Navy) and Orlando Agosti (of the Air Forces) entered the official box at 13:30. They had arrived by helicopter, the author points out. They shared the “honourable” space with FIFA’s president, João Havelange and his AFA peer, Alfredo Cantilo, one at each of Videla’s sides, and the porteño Cardinal Juan Carlos Aramburu.

That day, the Military Junta leaded by Videla decreed a national day off. While the chronicles of the time couldn’t agree on the number of spectators that attended the inaugural act (67 thousand, 75 thousand, 77 thousand people) the photographs and videos show the stands packed.

A fanfare of the Military School’s musical band. Another one. Clusters of colours floating up and in the giant stadium screen, the start signal: “Welcome to the XI football world championship FIFA World Cup Argentina 78”. The playing field filled with high school students, the real protagonists of the celebration, who entered the field marching from the laterals where they waited formed in line.

“Joy fills the space in a true manifestation of a country that receives the world” the announcer recites. He continues. “Quickly, with order and discipline in the conscience and the actioning, a word is drawn on the playing field: Argentina 78”. It’s the students who, following the rhythm of the military melodies, write with their bodies, distributed on the field, curled up like turtles, the allegorical word. They will then change to “Mundial FIFA”.

The journalistic records of the time mention that the participants of this choreographed “spectacle” structured around the “one two three four” of the platoons, were between 1700 and 1800 teenagers of 36 different porteño schools, both private and public, dressed in white and light blue. One of the people in charge, professor Beatriz Marty de Zamparolo, reaffirmed the idea before Somos magazine: “Everything was timed to the extreme. 120 steps per minute, 160 trots per minute, and a chord per second to take position. That’s how we could do everything in the 52 minutes and a half that had been assigned to us”.

Marty de Zamparolo coordinated the choreography along with the then national director of Physical Education of the Nation, Héctor Barovero. The professor mentioned in an interview that the idea had been proposed by the Ministry of Education to the 1978 World Cup Autarchic Entity (Ente Autárquico Mundial 78, EAM) who “accepted the idea and took care of the costs”. Coordinated by the teachers (La Nación informed that they were 54 in total), the students practised during almost a year “in various sporting fields, but particularly at the Palermo camping of the Gimnasia y Esgrima Club”, detailed Somos magazine.

For the members of the dictatorial government, the championship was a tool to “clean” the country’s face before the world in a moment in which the reports which described the persecution, kidnapping, torturing and murdering of political and trade-union, social and student militants, in secret concentration camps, were resonating more and more strongly.

To accomplish this objective, they developed a powerful press campaign that acted on multiple fronts and served as a “counter-campaign” to the Boycotting of the World Cup deployed by survivours based in Europe and many famous personalities from different countries committed to human rights. Maybe the crudest thing was seen in mass media.

Excluding some rare exceptions (the Buenos Aires Herald being the most important), the pages of newspapers and magazines, just like the TV broadcasts, did nothing but praise the organisation of the championship and, by consequence, the dictatorship.

They remarked, for example, that during the inaugural ceremony there were ushers with “yellow sweatshirts” in the stands who “bent over backwards to accommodate” the public; that bilingual stewardesses and cadets helped the press, that getting to the stadium “wasn’t difficult for anyone”; that the spectators entered “as if they entered the cinema on a Monday at 2 in the afternoon, without pushing, running nor flooding” and they left “as if they were leaving the Colón Theatre”.

The inaugural ceremony also counted with the releasing of white doves that “come alive in wonderful flight, leave as messengers carrying our salute in a symbol, peace”, mentioned the “feast”’s announcer. “Peace”, curiously, was reiterated insistently in the official discourses that were heard that afternoon in the Monumental.

“Welcome to the magnum world football competition and to this land of peace, liberty and justice”, read from a yellowed paper AFA's president, Alfredo Cantilo. At his turn, and far from digging into the declarations reporting atrocious crimes, FIFA’s president, João Havelange, spoke about the importance of football and stressed Argentina, “that great nation”’s, organisational capability. “We rejoice with this magnificent spectacle” he claimed, in hardly fluid spanish. Lastly, Videla spoke.

Morresi heard him with his uncle from the stands “that look to the river, where the River crowd stands today”. The official box, from where “the dictator, the murderer” spoke, was to his left. He remembers he stood “in silence, swallowing the rage” waiting for his speech to end: “I was there, stopping myself from shouting something, because somehow i realised that in different places of the stands there could be police dressed as civilians. I imagine if either my uncle or me had done something we would’ve been immediately detained”.

Videla allowed the applause that followed his presentation to resonate for a moment. He rubbed his hands, nervous, and started swaying on his feet. “Ladies, Gentlemen. Today is a joyous day for our country”, he began, his mouth twisting to the side.

His speech was short and, by his tone, he seemed to be speaking to a platoon of the Army he commanded. He spoke in the name of peace and the applause was grand. “I ask God for this event to truly be a contribution to the strengthening of peace, that same peace we all wish onto the whole world and onto all men of the world.” Thus was the championship inaugurated.