Omar Eduardo Torres arrived at the River court from one of the fabrics of horror: the Campo de Mayo military base, headquarter of, at least, four clandestine centres of detention. He dressed with black pants, a yellow sweatshirt, and stood on one of the accesses to the Monumental. Like him, hundreds of other men with the same uniform walked on the inside and outside of the stadium. “Those were the gendarmes”, Torres says, forty years later. He himself belonged to the force until 1983; the next year he presented before the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas, CONADEP) to denounce the crimes he had witnessed in Tucumán and in the clandestine centre El Olimpo in the porteño neighbourhood of Floresta.

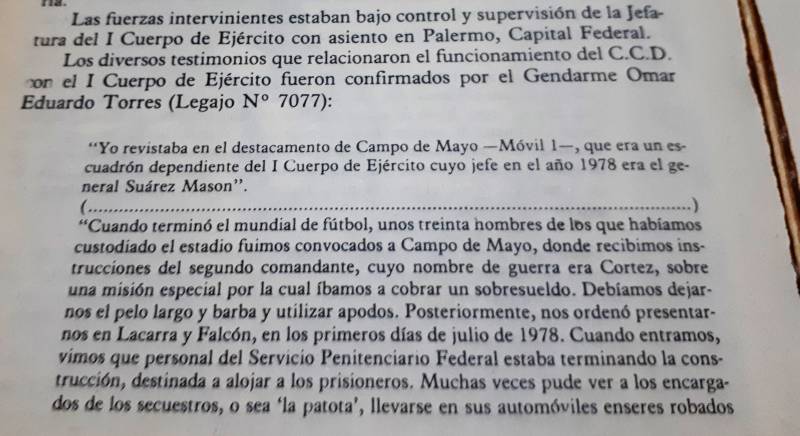

In the Nunca Más, the report that the CONADEP published, a fragment of Torres’ allegations can be read, in which he says that he had been in service as security in River during the 78 World Cup and that, once the World Cup was over, he was sent to the clandestine centre that was to be opened in the lot located between the streets Lacarra and Ramón Falcón: el Olimpo (Olympus), a place that was very far from being the home of the gods.

Fragmento de la declaración de Torres en el informe Nunca Más.

Fragmento de la declaración de Torres en el informe Nunca Más.

During those years, Torres declared in the trials for crimes against humanity and pointed the existence of clandestine pits in Tucumán, becoming one of the few uniformed men willing to collaborate and give information on the victims and also on his superiors and colleagues, the perpetrators.

The days of the World Cup

He lives in Salta and, from there, he accepts a telephonic communication to talk about the days of the World Cup and confirm that the dictatorship had extended its control during the days in which football was the nation’s main concern.

Born in 1953 in Buenos Aires province, he had been in the Gendarmerie for three years when they informed him that his next destination would be the Monumental to work on the security of the main stadium for the 78 World Cup. According to his story, the 800 men who integrated Gendarmerie’s Mobil Detachment 1 with base in Campo de Mayo were designated to River Plate and Vélez Sarsfield’s pitches. They arrived around two months before the inauguration ceremony of the 1st of June 1978, to take care of the security of the stadium in which dictator Jorge Rafael Videla was to welcome what the dictatorship would define as “the Cup of Peace”.

Torres was always assigned Núñez (where River Plate’s field is), wearing a yellow sweatshirt and black pants. “They gave the sector head, who were mostly petty officers, a black suit. They acted as ushers, but were actually security”, he recounts. According to Torres, the heads allowed him to have longer hair, a moustache or a beard while they were in the Monumental so that he’d lose the “military look”.

During those days there were no precise orders. They had to do what it’s usually done in those cases: take care of the place and see that no one came out of the field with suspicious lumps. Look and check. “They selected us for each place depending on our personality. I played dumb and obeyed”.

Jugadores entran a la cancha en el Monumental. (AR_AGN_DDF)

Jugadores entran a la cancha en el Monumental. (AR_AGN_DDF)

He alternated his position in the entry and in River’s ring. He could watch two games from the field, the one on June 10th 1978, in which the national team was beat by Italy, and the one on June 25th 1978, when Argentina won its first World Cup. “I had to be in the ring, but seeing as the Federal Police was there and the agents knew us, they let us through. There were a ton of others like me”, he explains.

The World Cup was over. The Argentine people went to the street to celebrate the sporting feat. There was joy, singing, paper rain and flags. However, the torture and death machine didn’t stop for a single moment.

A place with no gods

Gendarmerie’s Mobile Detachment 1 to which Torres belonged depended on the 1st Army Corps, under the responsibility of Carlos Guillermo Suárez Mason, but it had its headquarters in Campo de Mayo, which was a part of the 4th Army Corps. When the Cup was over, Torres and around 30 other men were called in to Campo de Mayo It was Guillermo Cardozo —alias Cortez— the one who told them they’d have a special mission for which they’d earn an oversalary. They had to let their hair grow out and use nicknames. The mission had to be fulfilled on the neighbourhood of Floresta, more specifically on a lot located in Lacarra and Ramón Falcón. “They told us we had to go to a place, but they didn’t say which place. I could imagine —he says—. I had already been in Tucumán. There they incinerated the bodies inside the arsenal company”.

He had first arrived in Tucumán between March and April 1976 —as his declaration to the CONADEP says. He came back twice —according to his testimony. In the meantime, he served in Campo de Mayo. There he guarded the kidnapped people in the Military Hospital and entered Campito, one of the clandestine centres that operated on that military garrison.

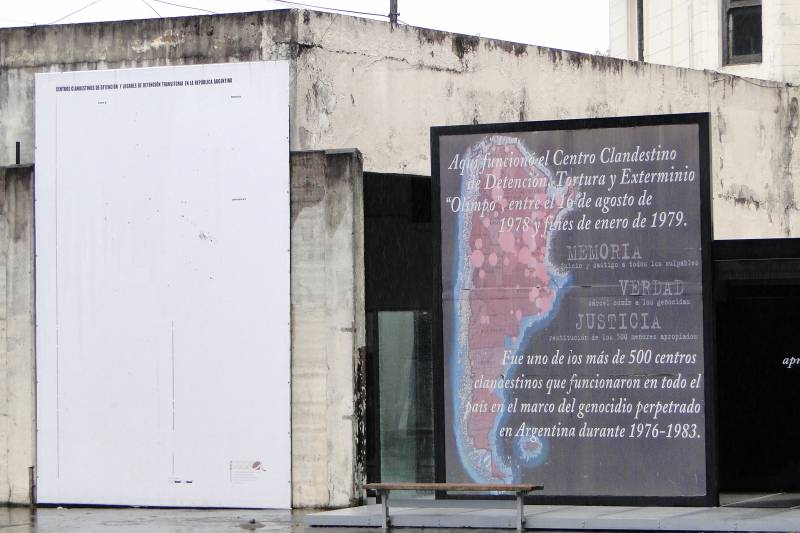

Entre 1978 y 1979, el Olimpo funcionó como centro clandestino en el barrio de Floresta.

Entre 1978 y 1979, el Olimpo funcionó como centro clandestino en el barrio de Floresta.

Cardozo, Torres’ superior, confirmed years later before the judges what the former gendarme had recounted. They had been dedicated to the security of River’s stadium and, once it was over, it was colonel Roberto Roualdes th one who entrusted him with the security of El Olimpo.

In July 1978, Torres was already serving in Floresta. When the gendarmes arrived, all the remodelling in the plot that depended of the Federal Police was already done: places to hold the captives and torture chambers, amongst other renovations. It was only a matter of waiting for the prisoners to arrive from “El Banco” and the mob that had Julio Simón, more sadly famous as “El Turco Julián”, as an emblem. During the 90s, Simón used to frequent television shows bragging about his crimes, but because of a cause that was carried out by the Centre of Legal and Social Studios (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, CELS) his case was used to declare the unconstitutionality of the Acts of Due Obedience and Clean Slate, and reopen the causes for crimes against humanity in 2001.

Torres was witness to the crimes in Olimpo, which operated until towards the end of January 1979. Once his task there was over, he asked to be relocated. He went to the provinces. He says he wanted to be as far away as possible. He left the Gendarmerie when the democracy came. By 1984, he lived in the Capital and worked as an employee. He presented before the CONADEP to present a complaint, he was asked if he wanted to do it with his first and last name, he asked for a day to think about it. “Whatever happens, happens”, he told himself, and spoke.

“I didn’t commit any crimes —insists the former gendarme who went through at least four clandestine centres. The only crime I committed was that, when seeing so many atrocities, I couldn’t tell anyone in that moment. This will remain in my head until the day I die”.