Mario Ramón Jofré was only 19 years old when the repressors of the dictatorship caught him in the ‘78 World Cup Press Center that had been installed in the Jockey Club building downtown Córdoba. Fascinated with the idea of sharing pictures of the matches with foreign journalists, Mario pretended to be one of them sputtering the scant Portuguese he had learned from Brazilian comrades who had arrived at their secondary school in San Luis.

“It was a Sunday, in May. I was studying to get to the Economics Schools at the University (National of Córdoba). I lived in the Alberdi neighborhood with my older brother who was already in Agronomy School and had gone on a weekend trip to the mountains. I didn´t go, but I went for a walk and arrived at the Press Center. There I saw all the people outside the building and I avoided the surveillance services. When I got inside, I started watching TV. Just about ten minutes later, two men approached me. One of them, jabbing my back, told me: 'You come with us.' That's where everything started.”

“Everything” was more than 45 days of captivity, torture and terror, “plus all the years of the trauma me and my family have suffered because of what happened to me”. Mario's voice sounds sure in the story, but the words come quick to his mouth when he tries to explain that “I had no political participation at all, they took me for the fun of it. When they released me, people all looked at me like saying “He must have done something”. I suffered a lot. And my family too. I became hypersensitive. Other people, with militancy, I think they could handle it better.”

–What happened after those two men took you?

–They put me in a room where with three men in plain clothes. I recognized one of them. He was from San Luis. I had seen him before. Much later I learned that it was Bruno Laborda (one of the accused in the La Perla-Campo de La Ribera Megacause). I looked at him and told him that it only was a childish prank, that they let me go. They questioned me, who I had come with, what organization I was, these things... I was desperated, but Laborda said that he was following orders and they put me in a Renault 4. We made a few blocks and they threw me in the back with my jean jacket on my head.

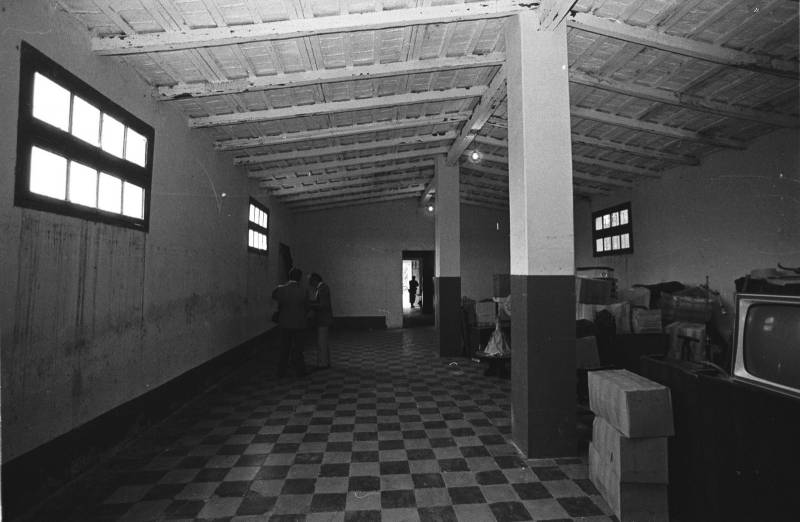

La Perla Chica. Inspección Conadep (Archivo Fotográfico Espacio para la Memoria La Perla)

La Perla Chica. Inspección Conadep (Archivo Fotográfico Espacio para la Memoria La Perla)

Mario remembered that his whole body was trembling, “I was terrified. I wasn´t aware of what the coup had been, nothing. I was a kid from the province.” The men, “in plain clothes”, took him near the Parque Sarmiento, where the 141th Battalion was operating. There, “I calmed down when I saw the military. I thought I would be safe... But no, everything got worse.” The interrogations were harder. They even took him to the courtyard, put him on his knees and gave him a mock shooting: “They triggered me four or five times with an unloaded weapon, but I felt it in my head. I trembled like a leaf, I cried like a baby. I couldn´t believe what was happening to me. They beat me.”

Hours later he was thrown into the back of a Unimog, handcuffed and hooded. The now 58 years old victim explains that halfway they opened the box of the truck and threw a person who fell upon me. He was also tied. This person was gasping, complaining of pain. I wasn´t alone. There were more people and also soldiers. The destination was what is known as "La Escuelita" or "La Perla Chica": a series of colonial-style buildings in the Malagueño area, to the left of the old road to Carlos Paz.

“There I was always blindfolded and lying on an alfalfa mattress. At night I could feel the cars on the road, but also the terrible cries of the people, tortured men and women, barking dogs, shootings. They took me out several times and they used electricity on my gums, on my genitals, they kicked my head... From all that I had a diverted nasal septum, two inguinal hernias, psychological disorders, nightmares... Not knowing if they're going to kill you, that´s the worst suffering... I was taken to the bathroom once a day. I had to hold in the urge to pee. In those times I got to see people who were lying like me, resigned. They also tortured me by telling me that if I didn´t talk, my family would suffer more. That they were having a bad time.”

- Did you ask if they were looking for you?

- No, I was incommunicado. But outside my family did what they could. I had an aunt who worked in the Archbishopric of San Luis, and she asked the bishop, Monsignor (Juan Rodolfo) Laise, ask for me. He was a patient of my cousin Víctor Luján, who was a dentist. Laise told my dad that I was alive. In Cordoba, my brother was looking for me. When he came back from his weekend trip, he realized that I was disappeared. He saw that there were guys hanging around our apartment and faced them. He even grabbed one of them from the lapels and didn´t let him go until he told him I was in custody.

More than a month after the kidnapping, the intervention of the bishop gave results: together with a soldier from San Luis, they called Mario's father one Monday and they told him “he is alive and in 48 hours He is going to be set free. And so it was.”

Mario has memories of the cold and the humidity of the confinement. From his desperation and hunger: “They gave us a soup with a bone. Only once did they give me a cooked meal... But in the last two days they treated me well. I ate bread with cheese and cold cuts.”

La Perla Chica. Inspección Conadep (Archivo Fotográfico Espacio para la Memoria La Perla)

La Perla Chica. Inspección Conadep (Archivo Fotográfico Espacio para la Memoria La Perla)

During the Megacause in Córdoba, when he testified before the Court in October 2014, Mario remarked: “A day or two before they released me, they took me out to the courtyard to sunbathe. They told me I was very white... There they took off my blindfold and I saw the first person in all that time: a squatting girl who had a skirt. She was very young, like me, or maybe a little older. She was kind of absent. She didn´t even look at me. Then they took her back inside. I don´t know her name. I only remember that she had white skin, black hair, curlers. They took her. It seems that they were treating her as well as me. But she was broken, without bathing, emaciated, sad, lost.”

One or two days later they took me to a Unimog and left me on the side of a road. “There the repressors repeated the modus operandi that they used for the liberated: "A military man with a hierarchical voice told me to count to one hundred and only the take off the hood and start walking.” And of course, the order to forget everything "forever". That he doesn´t tell anyone what he had suffered.

“It was noon. You don´t know what it is like to feel free at last...– he says, and the voice still breaks four decades later–. I hitchhiked but I was so dirty, in such a bad condition, that nobody wanted to stop. I had not bathed in all that time. It must be horrible to see me... As nobody stopped, I stood in the middle of the route and a truck had no other option but to stop. I told that man that I was harmless, asked if he would please take me to Córdoba. He let me get in for a ride and left me in downtown Córdoba. There I took a bus but didn´t have a dime. I had no money. But it seems the driver felt pity for me and took me to my neighborhood sitting in the first seat without making me any question."

Mario Jofré is relieved that his father didn´t reproach him at all. “San Luis was a very small society, we were about 60 thousand people and we all knew each other. The fact that they arrested me was a terrible stain for the family. There was suspicion. But they supported me. And I preferred to stay and study in Córdoba. I overcame fear... But I became distrustful of everything and everyone. It was very hard to be around me. It took me about nine years to move on.”

I didn´t disappear

Unlike most victims, who testified about what happened during the repression as soon as democracy was recovered, Mario took more time. “Look, I wanted to leave all that behind to move on. But one day in 2004, I was in a bar and red in Página / 12 Bruno Laborda´s complaints. Those in which he said all the things he had done during the dictatorship while complaining because he hadn´t been promoted. And he was also talking about me! He didn´t name me, but he said he arrested a student from San Luis who was disappeared. He told that student could be found cut to pieces in the La Rioja´s salt mines. That's when I jumped and said “I am that student and I´m alive!”

The denouncement of Mario Ramón Jofré, with the assistance of the lawyer María Elba Martínez, dean in human rights in Córdoba, was filed on June 28, 2004 in the Federal Court of Cristina Garzón de Lascano, and before the prosecutor Graciela López de Filoñuk.

The detonator was a twelve pages letter dated May 10 of that year, in which the then lieutenant colonel Guillermo Bruno Laborda complained to the Army Chief, Roberto Bendini, that he had not been promoted in spite of everything that He had done during the repression led by Luciano Benjamín Menéndez. In the letter Laborda detailed “facts that were not in my record of services or any other written document.” He thought his superiors had not promoted him or increased his salary maybe because they didn´t know those facts.

Determined to reverse what he considered an injustice, Laborda related with almost surgical precision, atrocious crimes. Among those “acts of service”, which were nothing but crimes against humanity, stood out the execution of a young woman (Rita Alés de Espíndola) who had given birth to a baby a few hours before a platoon in charge of Laborda riddled her “with twenty bullets”, while she was “kneeling in a nightgown and blindfolded”. “According to the repressor, “she was sentenced to death because of her proven actions in acts of sabotage in the development of the ‘78 World Football Championship.” Laborda described: “The transfer to the firing squad of the Garrison was the most traumatic thing that I had to feel in my life: despair, continuous weeping, the stench of the adrenaline that emanates from those who face their end, their desperate cries imploring that if We really were Christians, we swore them that we were not going to kill them…, it was the most anguishing and sad thing that I felt in my life and that I will never forget.”

Both Laborda and his colleague Ernesto "Nabo" Barreiro –who wrote to the dictator Jorge Rafael Videla on April 30, 1977– they self-incriminated themselves with their own handwriting. Such was the feeling of impunity of the repressors led by the genocidal Luciano Benjamín Menéndez, in charge of the repression in Córdoba and others Argentine provinces.

Laborda couldn´t ignore that he had violated human rights, that he had committed crimes against humanity. He was already a lawyer when he sent his letter to Bendini where he admits “ having participated actively and in conjunction with all the Officers of my Unit in the year 1979, in the removal of the corpses buried in the “Campo de la Guarnición Militar de Córdoba”, product all of them of the so-called "Final Regulations" (...) In those years, the effect on the soul, the spirit and the psyche of all of those who, without any preparation for this type of task, collected human bodies for days has no measure rationally established to measure the psychic impact produced to all of us who consider ourselves Christians. With the participation of specialized personnel and machinery of (Batallón) 141, the bodies were compacted in containers and then spread in tiny pieces, in a saline near the city of La Rioja”.

In the case of Mario Ramón Jofré, Bruno Laborda thought that he was a disappeared he thrown into those common graves of the fields of La Perla. That his bones, “the size of a coin”, as described by the repressor Héctor Pedro Vergez, traveled compacted in one of the 20-liter buckets that ended up scattered in the Rioja salt mines so that they disappear forever. “Surely his corpse or what is left of it”, Laborda wrote, “is today part of the bleak landscape that characterizes the Riojan salt mines."

Mario didn´t meet the repressor again. Laborda died of cancer in July 2013 during the development of the La Perla-Campo de La Ribera Megacause; and the victim declared only in October 2014.

Barely a teenager when he was caught –“because the inexperience or immaturity of his youth”– as the genocide himself admitted in his 2004 claim– Mario Jofré had the courage to point him out and gave testimony about what he suffered every time he was requested.

“I've remade my life: I have a job, I'm a father, a grandpa, that's my best achievement.” But there is still a way to go on the subject. The man closes the interview with a claim “I have not been able to achieve an economic compensation from the State. Yes, I had the satisfaction of Justice, of closing that circle. But a State that became a terrorist must repair its victims. In this or in any government. It is not a gift. It is a repair here and in any other country. That's what I still hope, and I will not stop trying to achieve."