In July 1977, eleven months before the World Cup was celebrated in Argentina, the ambassador Tomás de Anchorena received 100 thousand dollars to mount an office in Paris to counteract the accusations of grave human rights violations being committed in the country. That’s how the Pilot Centre of Paris was born, as an arm of the task group of the Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA) in the Old Continent. It was a parallel embassy in the French capital, where two practices were combined: the infiltrating of groups opposed to the dictatorship, and the military government’s propaganda.

Member of a patrician family and an ex-member of the Army, Anchorena had arrived in the French capital after a request from Jorge Rafael Videla in 1976. His profound disdain for peronism had gotten him close to the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR). He had to ask for the authorization of the then leader of the party, Ricardo Balbín to accept the offer of the dictator, as retold by journalist Daniel Gutman in his book Somos derechos y humanos.

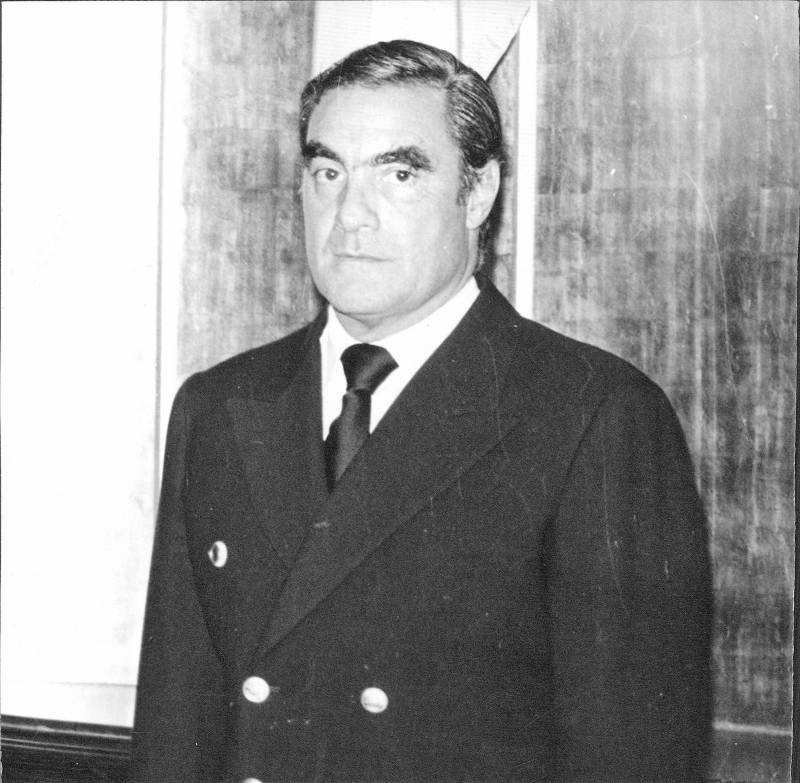

The myths about the origin of the Pilot Centre are two. According to Anchorena, it was created after an ambassador meeting that he himself called, and as a response to what they perceived as a rising campaign against the country. The encounter had taken place in Paris in March 1977. “The initiative was mine”, he told the judges in the Trial to the Juntas of 1985. The other version —collected by journalist Andrea Basconi in the book Elena Holemberg: la mujer que sabía demasiado— is that the Centre was built with the help of admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera, after a trip to Europe in which he set to attract attention as the saviour of Argentina, and instead ended up being overshadowed by the accusations of kidnapping, forced disappearances and torture.

What’s true is that the Pilot Centre was created the 26th of July 1977 through Decree No. 1871, signed by Videla himself, by the then chancellor Oscar Montes —a key ally of Massera’s— and by the Ministry of Economy José Martínez de Hoz. Depending of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship, the Directorate of News and Public Information was created so as to save Argentina’s face. There were three areas depending from that Directorate: the Press Department, the Foreign Dissemination Department, and the Pilot Centre itself, that was meant to spread the dictatorship’s message to other countries in Europe.

The first directive of diffussion abroad sent the 15th of August 1977 by Navy Commander Roberto Pérez Froio, in charge of the press directorate of the chancellery, left clear that Argentina had to pay attention to mainly two fronts: European social democracy, and the Democratic Party of the United States, that in January of that year had reached the White House in the hands of Jimmy Carter. The Pilot Centre was to dedicate itself to the European reality. The task that was detailed in section number nine concretely had as a main objective the championship that was to be carried out: exploit for all of Europe the media linked to the 78 World Cup.

Why Paris? Because that’s where a strong protest movement against the dictatorship had developed and where the Committee for the Boycott of Argentina’s Organising of the World Cup 78 (COBA) had been born. During the time it was active, the Pilot Centre was invariably linked to the World Cup and Massera’s international projection.

The Pilot Centre in action

Anchorena rented in July 1977 a property located in 83 avenue Henri Martin and began organising the offices that would be witness one of the most sordid internal machinations of the Military Junta. At the time, Pérez Froio had travelled to France on official business, as stipulated by a secret resolution of the Chancellery on the 13th of July of that year. The director of Press of the Chancellery arrived in the French capital on the 20th of July and was there for nearly fifteen days. He travelled to settle important details and the de facto government gave him three thousand dollars with the obligation of rendering the costs.

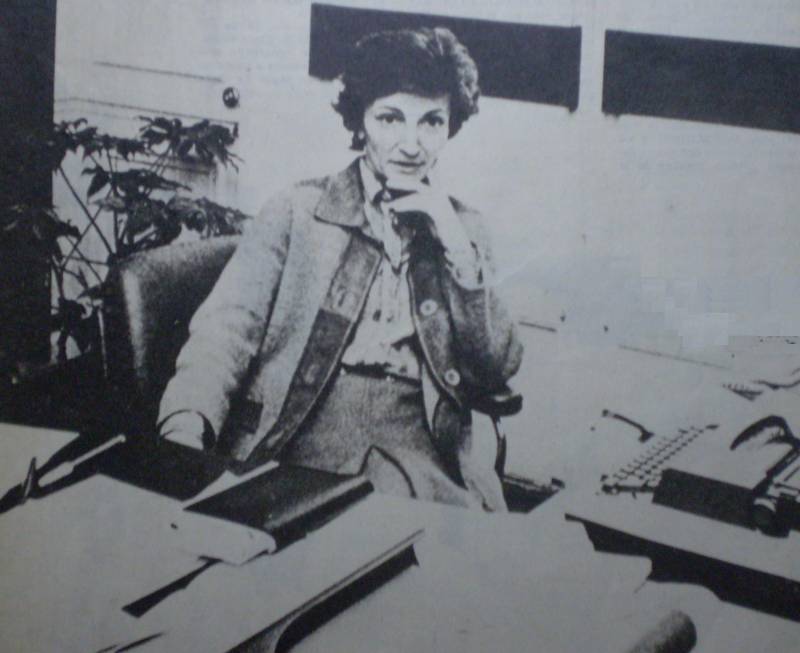

The Pilot Centre had a double dependency: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Argentine Embassy in France. Anchorena had powers other than settling leases. The first thing he did in relation to the Pilot Centre was designate the career diplomat Elena Holmberg as the responsible for that office, a strong defender of the dictatorship and, like Anchorena himself, allied to the Army's interests.

According the the former ambassador in Paris, life in the Pilot Centre went on in relative harmony with its ends until the arrival by the beginning of 1978 of the first ESMA committee: the navy lieutenant commander Eugenio Vilardo and the Chief of Boat Enrique Carlos Yon. According to a resolution by the Chancellery on the 12th of January 1978, the two navy men were sent to the city of lights because the tasks of the Pilot Centre “can't all be taken up by the Embassy personnel that is at the moment overcharged by their specific tasks”.

According to the order imparted by chancellor Montes, they knew when Vilardo and Yon’s mission would begin, but not when it would end. Yon had to be in Paris from January the 22nd of that year, and Vilardo from February the 15th. The two of them quickly gained the disdain of Holmberg and Anchorena, who made it clear that what took those two to Paris wasn’t the “anti-argentine campaign”, but rather Massera's interests, or the realisation of the ESMA’s activities in other latitudes.

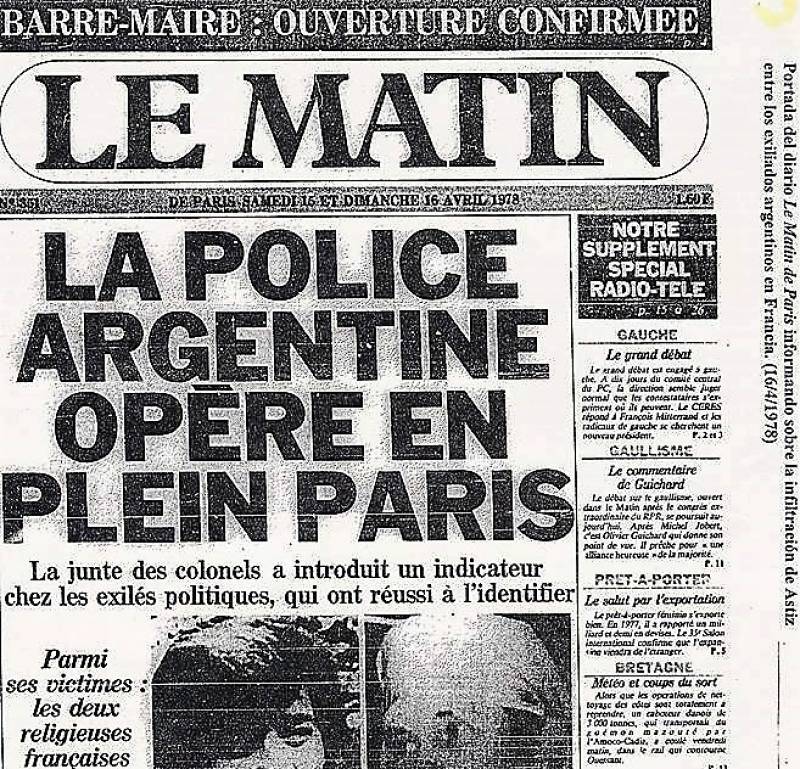

Periódico Le Matin del 15 y 16 de abril de 1978 denuncia la presencia de Astiz. (Gentileza de Canal Abierto).

Periódico Le Matin del 15 y 16 de abril de 1978 denuncia la presencia de Astiz. (Gentileza de Canal Abierto).

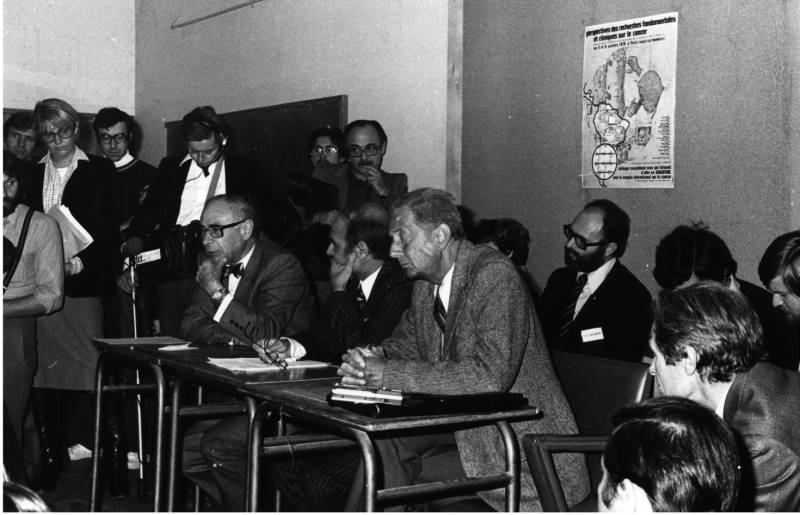

Durign that same time it was reported that Alfredo Astiz had arrived in Paris. He came from infiltrating the movement of relatives of disappeared, that had ended in December 1977 with the kidnapping of the founders of Madres de Plaza de Mayo and the French nuns Alice Domon and Leonié Duquet. In April 1978, the newspaper Liberation —founded by Jean Paul Sartre— published that there were Argentine military men trying to infiltrate the exiled movement. Le Matin did the same thing. A photograph donated by Gabriel Periés to Horacio Verbitsky demonstrated that Astiz, under the fake name Alberto Escudero, had remained close to the Argentine Committeé of Information and Solidarity (Comité Argentino de Información y Solidaridad, CAIS), until October of that year.

En el margen izquierdo, Alfredo Astiz participa de una reunión de exiliados argentinos en París en octubre de 1978.

En el margen izquierdo, Alfredo Astiz participa de una reunión de exiliados argentinos en París en octubre de 1978.

Antonio Pernías, alias El Rata, had also arrived in France by March 1978. Pernías was part of the settled torture staff of the ESMA. Before him, Jorge Perrén, who operated in the Pilot Centre under the alias of Juan Martín Aranda, had also been assigned to Paris. Seeing as the offices of the Henri Martin Avenue were an extension of the clandestine centre located in the Avenida del Libertador, they also took to the Pilot Centre three kidnapped women, who were more capable with French and doing press work than the perpetrators themselves. They were presented to Holmberg as sociologists and they didn't share her office, instead being forced to work in a house in the rue de Loche.

The World Cup at the Centre

In June 1978 the World Cup was to be played in Argentina. In France, the game was another. By then, the internal fight between the Army and the Navy had detonated in the Pilot Centre. Vilardo had exploded in fury against Anchorena and decided to send Pérez Froio a letter to inform him that the ambassador was to give an interview in the radio station France Inter, that had once before interviewed “subversive exilees”.

Elena Holmberg. (Siete Días, septiembre de 1982)

Elena Holmberg. (Siete Días, septiembre de 1982)

By then, Holemberg was no longer in France. Following the 831 resolution, the chancellor Montes had ordered that she be back in Buenos Aires by May 1978. Friends and family of the diplomat —who had good connections to another of the dictatorship's factions— insist that the reason of her return was linked to the fact that she reported that in France a truce had been negotiated between Montoneros and Massera during the World Cup. The other reason that could, in reality, have accelerated her return, was that she had become a bothersome witness of the handling of money and the aims of the Pilot Centre, which was progressively turning into Massera’s action platform to win international prestige.

The 4th of June, while visiting Mar del Plata right in the middle of the World Cup, Massera announced that he would in a couple of months leave the command of the Navy in the hands of Armando Lambruschini. That was the first step towards presenting himself as a “democratic” alternative against the dictatorship and as a social democratic option. In this announcement he strived to recognize that there had been mistakes made by the Military Junta, as was necessary for someone who wants to dissociate themselves from the criminal methodology of the de facto government of which he was a part of.

Emilio Eduardo Massera. (AR_AGN_DDF)

Emilio Eduardo Massera. (AR_AGN_DDF)

Primary responsible for the emblem of Argentina’s state terrorism, the ESMA, Massera used to tell his European interlocutors that the government should issue a list of the missing people. In June 28th 1978, three days after the conquering of the World Cup by the Argentine National Team, the news agency Noticias Argentinas echoed a rumour: the Military Junta considered the possibility of publishing the names of the people “struck down in the struggle waged by the Armed Forces against subversive terrorism”. What was the source? A senior official of the Navy, according to the dispatch. Probably no other navy man that wasn’t Massera himself would dare filter that version.

Massera retired in September 1978. By then he had created his newspaper, Convicción, that also functioned thanks to the slave work of victims of kidnapping in the ESMA. As told by Anchorena in the Trial to the Juntas, he dismounted the Pilot Centre of Paris in October. Its first manager, Elena Holmberg, was kidnapped in Buenos Aires in December the 20th of that same year at the garage door found in the street Uruguay 1055. Three men wrestled to get her into a light blue Chevy. Everyone saw in this kidnapping the methodology of the ESMA's mob. The lifeless body of the 47 year old woman appeared two days later in the waters of the Luján River in Tigre, in jurisdiction of the prefecture, a force that at the time reported to the Navy. Her family only found out about the body’s discovery in January. As held by journalist Andrea Basconi, it continues to be a paradox that she suffered that end, she who had worked so hard from the Pilot Centre so that “the true Argentina was known”: with no torture, no forced disappearances nor bodies floating in the rivers.