“Things didn’t really work out for me... I must confess that I was completely calm.” René Houseman moped before the journalists after his poor performance in the national team’s first game of the 78 World Cup, against Hungary. Argentina had won 2 to 1, but the wing was news because of his underperformance. “Even though I keep thinking about it, I can’t figure out what happened”, he insisted.

Ever since this failed début, the striker sponsored by the Argentinian coach César Luis Menotti alternated between titular player and substitute. He had his revenge when he scored the fifth goal during the 6 to 0 against Peru and finalized the World Cup as he had begun it, in the field of the Monumental. There, a little over 20 blocks from where he had fed his dreams, in the Villa 29, a shanty town in Bajo Belgrano. Houseman lifted the Cup of the World when he was about to reach 25 years of age, but he could never celebrate on the neighbourhood that up until the day he died, was “his place in the world”, where his people were, because the military government had “erased” the villa. “They destroyed me from the inside”, he remembered in an interview in 2014 for the Cuadernos del Mundial initiative by the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales, CLACSO) and La Garganta Poderosa magazine.

The story of René, the story of feeling completely miserable, was the story of thousands of villeros and villeras, working families with low resources who had arrived mainly from the other provinces in the country or from bordering countries, who were victims of the Eradication Plan carried out by the civil-military dictatorship.

“The main fields of action were the villas 29 in Bajo Belgrano, 30 in Colegiales, 31 in Retiro, and 40 in Av. Córdoba and Jean Jaurés”, points out the investigator Demian Konfino in his book Patria Villera (2015), that says on Houseman’s neighbourhood: “It was very close to the nerve centre of sports and political tourism in the year 1978, and in an area of high purchasing power that didn’t want to mingle”. The plan would also extend to the slums of the south, like the Villa 15, that had a wall built around it when the eradication got delayed, giving place to the sad nickname of “Ciudad Oculta” (Hidden City).

If in 1976 there were 224 thousand people living in villas and settlements in Capital Federal, two years later, in the months following the ‘78 World Cup, close to 50% of those people had been expelled from their homes, according to the official report of the Municipal Housing Commission (Comisión Municipal de la Vivienda, CMV), quoted by Marta Bellardi and Aldo De Paula in Villas miseria: origen, erradicación y respuestas populares.

By June 1980, while mass murderer Jorge Rafael Videla continued leading the Military Junta, only 9 thousand families remained in the porteño settlements; and the number would go down to 4 thousand a year later. This systematic plan of expulsion was carried out with the total eradication of neighbourhoods such as the one in which René lived.

The political scientist and investigator of the Instituto de la Espacialidad Humana (FADU-UBA) Romina Barros makes clear that the Eradication Plan was designed based on the Ordinance 33.652 of April 1977, dictated by the Capital Federal controller Osvaldo Cacciatore. It was made out of three stages:

In the Capital Federal the plan had the holder of the CMV, Guillermo Del Cioppo as the executor arm, who argued that it was necessary to “deserve living in the city” and congratulated himself: “The problem was solved in a surgical way and in record time”.

For the dictators “the problem” was not the housing solution of working class families. The dictatorship’s Secretary of Housing, Máximo Vázquez Llona, informed in May 1978 that the housing deficit affected 42% of the Argentine population, then of 25 million, while he defended the execution of a new lending law that came into force five days after the end of the World Cup and allowed the eviction of 200 thousand people in Capital Federal alone. At the same time, the de facto government offered easy credit to hotel owning businessmen so that would build four and five stars hotels.

Then, the civic-military objective was to recover the city space for the growth of private real estate. A second goal, for the 78 World Cup, consisted of showing another “image of the country” before the FIFA authorities, the national teams and the tourists that would arrive.

While “the population of the villas was taken to the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area or deported to bordering countries”, as Barrios points out, papers and magazines focused on the constructions that were hampering traffic in the Capital’s centre. An article in Somos magazine titled “La fiebre de la piqueta” (pick-axe fever) shouted: “Since a couple of weeks ago, Buenos Aires looks like a bombarded city: tens of streets and avenues closed down, main traffic lights not working, traffic diversions through narrow, busted roads”.

The monumental Eradication Plan

“The measure comes about because an important section of the so-called Bajo Belgrano was substantially neglected when it comes to its urban development (...) by the persistence, over the last 40 years, of a shanty town”, the paper La Prensa transcribed in a short article the municipal ordinance that allowed the erasing, during the first months of 1978, of the 7 blocks in which two thousand families of the Bajo Belgrano villa lived, where champion Houseman’s home was once located.

With euphemisms such as “hurting urban development” and “leaving it to urban renovations”, the Cacciatore and Del Cioppo ordinances marched forward towards the civic-dictatorship objective of generating “the conditions for an urban growth of this sector in line with the area’s characteristics, through commercial and private initiative”.

Like so, the Eradication Plan continued with its bulldozers through the villa 30 in Colegiales and the 40, located in Córdoba Avenue and Jean Jaurés. Konfino, of Patria Villera, emphasizes that the villa 40 was the first to be eradicated, in August 1977, because only 95 people lived there, and the terrain quickly yielded results for the dictatorship’s tacit partners.

Meanwhile, in the villa 30 of Colegiales, another one that was completely eradicated prior to the 78 World Cup, the military expelled 2931 people. The old neighbourhood located in the intersection of the streets Álvarez Thomas and Matienzo is nowadays taken over by a transfer centre of the Metropolitan Area Ecological Coordination State Society (Coordinación Ecológica Área Metropolitana Sociedad Del Estado, CEAMSE); some of the city’s rubbish is disposed of there.

From the Sheraton to the swamp

The Villa 31 in the neighbourhood of Retiro was the next step for the Eradication Plan. The neighbourhood occupied 32 hectares in 1976 and housed six thousand families, according to the official data of the CMV. Located in the territories bordering the Mitre train station, where it remains to this day, it was the home of 24 thousand people who could see the Sheraton international hotel from their compartments. But by 1978, when the five star building accommodated the duth players for the World Cup final, the eradication plan was steadily advancing over the villa 31, under the direction of Chief Inspector Osvaldo Salvador Lotito. Konfino reviews in Patria Villera how Lotito described his tasks. “When there’s an operation there’s always blood”.

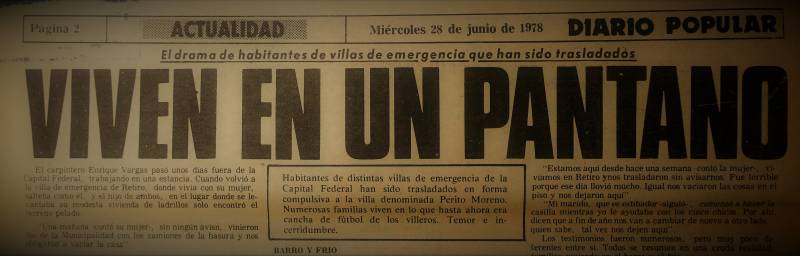

The official CMV numbers show that by December 1978 only 2 thousand people remained in the 31. Such a plan of expulsion was not denounced by the local papers, other than to complain about the “presence (of displaced people) in one or other jurisdiction, stigmatizing them to no end” describes Konfino. However, once the 78 World Cup was over, the 28th of June, three days before the celebration, Diario Popular published an article under the title: “They live in a swamp”. The swamp was far from the Capital Federal, in La Matanza, where some improvised tin-roofed houses had advanced over the small football field of Perito Moreno’s villa. The article showed the Eradication Plan from a first person account.

“I have two children and my husband is disabled. (...) One morning they dismantled the house we had in Retiro, took everything in garbage trucks and took us here”, Margarita Miranda told the paper, and said she had been living in the middle of the La Matanza mud for less than a month. The woman had missed, while moving, Houseman’s poor début.

“With maces and iron bars they took our home apart, leaving nothing behind. They brought us here, they threw our things on the floor and they left, after preventing us that if we made a scandal or complained they were going to put us in prison”, another woman recounted. Along with their belongings, the dictatorship was throwing the displaced an economical assistance that wasn’t enough to pay for even the first fee of a plot or to install a water pump.

The Dutch players recounted, after their defeat, seeing the celebration of the Argentine fans in the streets from the windows of the Sheraton. Diario Popular’s chronicle, published three days after, offers a painting of what was happening in front of the five star hotel: “In the Retiro villa, where the eviction operation is now centred, wide extensions of terrain can be seen covered by the rubble of what used to be the homes of displaced families”.

Ciudad Oculta (Hidden City)

Far from the city centre’s lights, almost on the border chosen by Cacciatore, the villa 15 started growing towards the end of the forties and by 1976 it occupied almost four blocks. It’s location in-between the neighbourhoods of Lugano and Mataderos didn’t signify a problem for the “country image” the dictatorship was looking after, who’s “main preoccupation was to show all the northern area of the city free of these working class population isles”, Barrios claims.

However, the neighbourhood held a dangerous place for the military’s objective: Avenida Del Trabajo was one of the roads that would be taken by foreign authorities, national teams and tourists that would come from the Ezeiza International Airport to the centre of the city.

“What the dictatorship does is building a wall that allows them to cover up the villa, hiding that which they hadn’t managed to eradicate yet. The wall explains the impotency of not having been able to get to the southern villas because the plans for the south were definitely in another time priority”, analyses the investigator of the Instituto de Espacialidad Humana (FADU-UBA)

The wall that can still be seen over the avenue renamed Eva Perón is a current historic mark of those years of terror for the residents of the neighbourhood. The Eradicate Plan was a milestone for all the inhabitants of porteño villas, who counted with the brave resistance of the Pastoral Team of Shanty Towns (Equipo de Sacerdotes de Villas de Emergencia); and a practise that the dictatorship extended to other points of the country, like Rosario, in Santa Fe province, in which the Las Flores neighbourhood was nurtured by trucks of poor families brought from the centre of the city, where Argentina played the second group stage.

“I don’t like remembering the ‘78 because of what was happening in the country. Had I known what was going on I would’ve quit the National Team”, lamented René, afflicted by memories of being both a champion and an eradicated villero.