Mario Kempes runs and celebrates with both arms in high. Leopoldo Luque also lifts them up in excitement. Daniel Bertoni touches the net of the Dutch goal with his hands. The goalkeeper Jan Jongbloed satnds up and extends his arm looking for explanations. The defender Jan Poortvliet runs with anger against the right goalpost and his teammate Wim Suurbier runs in circle to get out of the mess Kempes left them with his goal. When 14 minutes of the second half of the final of the 78 World Cup had past, the Argentine team wins 2 to 1 and is on track to raise the trophy in a packed stadium.

But there is another story in that snapshot. A story that includes the thousands of Argentines who celebrate and, at the same time, make fun of the campaign mounted by the civic-military dictatorship to show “a good image to the world” amid the system of repression, arbitrary arrests, and the disappearance of people.

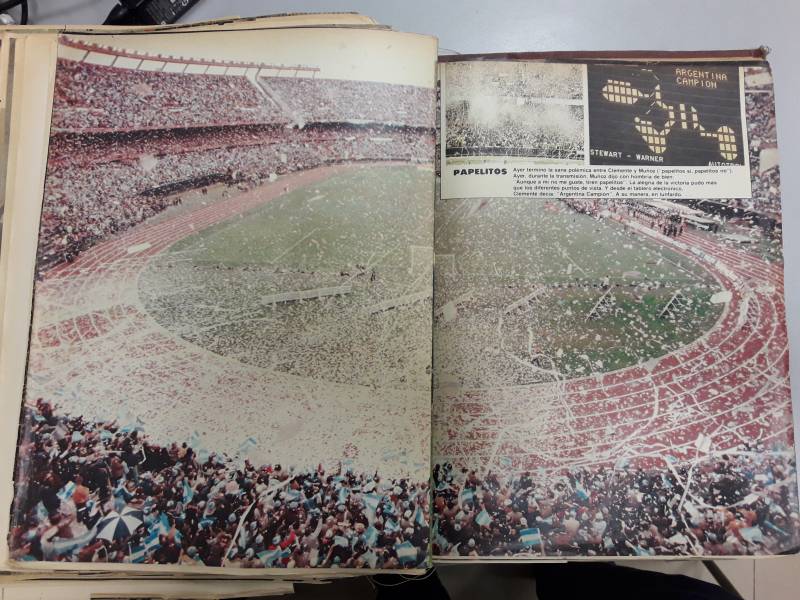

Hundreds of white spots can be seen on the field where the whole scene occurs. It is a rain of little papers, it is a message that has a guide: Clemente, who would become the mascot of popular expression, leaving aside the official mascot, the Gauchito with a whip in his right hand.

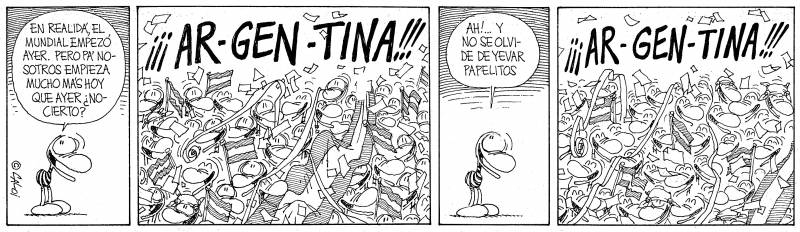

The father of the creature, similar to a striped bird with no wings, is Caloi, Carlos Loiseau. The comic strip was published in Clarín newspaper every day. While readers could find the news of the civic-military dictatorship campaign months before the World Cup –which ordered: “Mr. spectator: the country also plays on the field”, and that was concerned with “showing how ‘we really are,’” and encouraged “playing the “championship of good manners and fellowship "– Clemente reflected from the its comic strip: “You have to eradicate the confetti for the World Cup. We must avoid fights, aggressions, thefts, and scams, for the World Cup. (...) When I see that all this is done for the World Cup, I am grabbed by a scary thought ... What will become of us when the World Cup ends, the last tourist leaves and we are alone?”

Clemente warned argentines of the intention of the civic-military dictatorship to suspend reality, while from the abroad there were growing reports of human rights violations. He then launched his “paper rain campaign”. Clemente, created by Caloi in 1973, became “SuperClem” in some strips, with the goal of raising the cup, and found his nemesis: José María Muñoz. He was the most famous radio reporter of the moment and would go down in history as the official voice of that World Cup. He would be remembered that way because he took the “Argentina 78” campaign of the dictatorship as his own crusade. For the reporter, to take to the World Cup matches the tribune tradition of throwing confetti to receive the team would show Argentina as a dirty country.

“He saw the dirt only in there. And well, He left me “with the ball in front of the goal”, and I lashed out with the confetti campaign, which was a very colorful, very participative practice of the football fans. The songs and the confetti were the way people say 'present!'. This became a symbolic war,” recalled Caloi in one of his last interviews.

A cartoon against Muñoz

The confetti was a popular expression and also a break in the campaign of the Military Junta. “Haven´t we agree to preserve the country´s image?” He mocked from the comic strip to explain why he had renamed the National Team coach “Masotti” (a pun with the words “Más” –more, plus–, and Menos –minus, less– and Menotti´s name. “It sounds more like a winner,” he explained. He did it with other members of the coaching staff. The ironic rebaptisms was to transform them into something more “positive” according to de dictatorial campaign. But the pun with his nemesis name didn´t leave much room for the metaphor. In the Clemente strips, Muñoz was “Murioz” (Murió meaning “he dead”).

“How many times in a restaurant, in the street, from a bus, did someone shout: ‘How are you doing, Massotti?’” Recalls Menotti in the prologue of the book Clemente es Mundial (2013). He celebrates the “progressive message and forceful cultural resistance, indirectly combative, in a very hard time. Humor made it possible because those in power didn´t understand it: they believed that Clemente was only a cartoon” Menotti says. For María Verónica Ramírez, the plastic artist and companion of Caloi, that search went further: “It was not a minor thing that he called 'Massoti' to Menotti, it was so that none of us would be less”.

“What Caloi actually did was a modest transgression. To start a fight with Muñoz and call for the revolution of throwing confetti against the order that Muñoz was proclaiming was like a tiny victory of the transgression that we all wanted,” adds the journalist Juan José Panno. He worked with Caloi in El Gráfico football magazine (where Clemente was also published), and was renamed “Pannoti” by the creator of Clemente.

Caloi´s comic strip clashed with the editorial line of the newspaper that echoed the official discourse, as analyzed by Florencia Levín in his book Political humor in times of repression (2013). “Carrying out the World Cup constitutes a triumph on the subversion, which tried to break the morale of the country to prevent its realization”, says the editorial “World Championship” published in July 1977. “Caloi, guided by his own creature, tried to put a stop to the governmental manipulations,” says Levin in his study.

Levin points out that although there were few examples of censorship in Clarín newspaper, stories of “banned” comedians were known. Caloi had been part of them a group he called “La patota”: Crist, Roberto Fontanarrosa, Alberto Bróccoli, Horacio Altuna, Carlos Trillo. “I knew what the limits of censorship were so I didn´t not working for nothing, but there was a nefarious character there, who was Joaquín (Morales Solá). He said: 'That's won´t be published'” recalled Caloi.

“Confetti” hammers

“You saw that triumph the other day, right?” “Definitive, eh!”... “Yes, vs. France too, but vs. Murióz, I mean”, Clemente celebrated when Argentina was already heading to pass the first round. In all the stadiums, giant screens were installed with a primitive system of lights like pixels that allowed writing the teams' formations, the changes, and the goals. The control of that screen was in FIFA´s hands, the EAM 78, the official entity of the dictatorship didn´t controlled it. The technicians had asked Caloi to design a Clemente in pixels.

Unlike the stadium of the final, the Gigante de Arroyito has the stands stuck to the court, with no athletic track that separates them. Confetti and paper strips flooded the field; the voices of the stadium, under the control of the military, demanded the people not throw anything and threatened with the match suspension. Clemente, from the screen: “Throw Confetti, boys!”

The victories against “Murioz” would accompany those of the national team, match by match, despite the fact that “there were controls on the fields and the newspapers that people used to make confetti with were confiscated”, recalls María Verónica. In spite of this, when Captain Daniel Passarella put his foot on the field to lead the team, the paper rain was still happening. “There were mountains of papers next to the fences, in the entrances to the stadium,” mocked Clemente on Clarín.

“Tomorrow we continue the weirdness!” shouted Clemente in the preview of the final of Argentina against Holland in the Monumental stadium. It was the day of the final battle of the “confetti war”, between the popular joy and a Europeanized image. FIFA President João Havelange, a loyal ally of the Military Junta, had given up, but with a gesture to Muñoz. “There are no reasons other than hygiene to prevent the Argentines throwing confetti on the fields when their team comes out” he said in a "yes to the confetti" and added: “It is safer to throw confetti and not bottles.” A similar excuse would be used by the famous reporter several days after the end of the World Cup, to recognize his defeat. He would say that his fear was that “the wooden taquitos (little dowels)” of the rolls of paper would hurt some players.

“Lo digo yo/ lo dices tú/ tirar taquitos es una gran virtú” (I say it / you say it / throwing taquitos is a great virtue)” would answer a stand full of Clementes –a preview of the famous stand of Clementes that would be on television for the Spain 82 World Cup from the daily strip–. Without metaphors for "Murióz", after the song, in the comic strip, a team of military was seen jumping into the field.

Stands singings and confetti went hand in hand for Caloi, and that was also understood by the people. In the final –Caloi was in the Monumental stadium that day– from the stands was heard: "Murioz, Murioz, we throw confetti for you".

That exaltation of popular expression that the Military Junta sought to frame within its repressive parameters –silence is health– was Clemente´s victory. In another comic strip, he criticized the “sociologizers” of the World Cup and pointed out: “And there they go... trying to discover hidden meanings in the festivities. And the meaning is clear: the celebrations are the result of the joy that football produces. What else can be celebrated?”

“He was a very conscious guy, very committed to what he thought, to what he felt. Everyone always knew who he was and where he stood politically. The Negro did none of that naively. Maybe all this grew more than he thought it could grow. I think that at some point he should be scared, but the same visibility of Clemente protected him” María Verónica describes.

Clemente, who had asked “Masotti” to call him up for the World Cup team, even as a mascot, had already become the popular mascot of cultural resistance against the civic-military dictatorship. The quote “Throw confetti, boys!” appeared now in the screen of the Monumental stadium. Kempes scored the second goal. 14 minutes of the second halftime, the victory was imminent. The paper rain fell on the field.

On FIFA official website, 40 years later, there is an article entitled: “Kempes key as Argentina are crowned with confetti”.